|

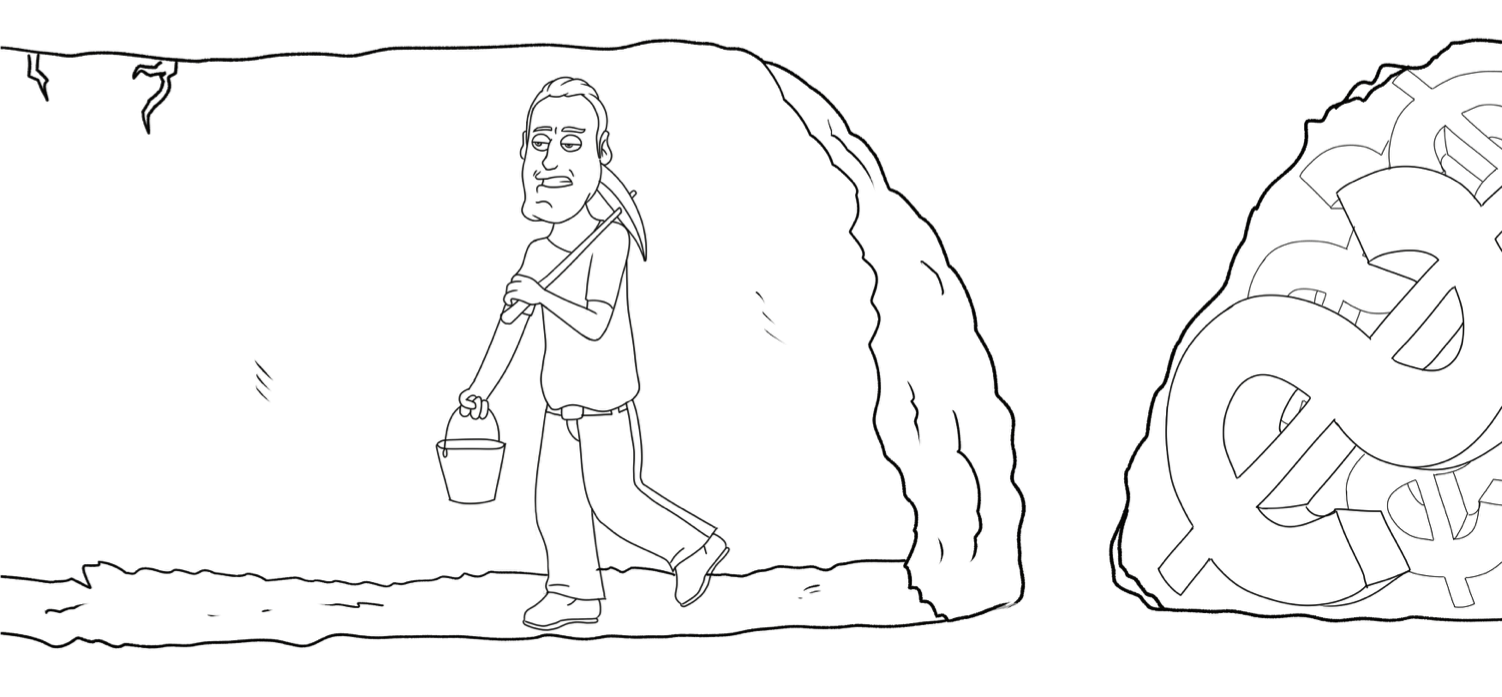

In pursuit of our goals, one of the most painful decisions we can face, is the possibility of failure. And given that we are hardwired to avoid pain, it is not uncommon for us to adopt a philosophy that to quit, to surrender, or to otherwise disengage from a goal is “unthinkable,” or “not an option”. This same philosophy is reinforced in certain cultural beliefs, such as in the power of positive thinking, the law of attraction, or in the unquestioned wisdom of a popular celebrity. (1) This is wrong, both scientifically and philosophically.While the science is clear that positive self-efficacy…a type of positive mindset…is a critical element for success, there are additional studies to consider. Research on goal achievement, motivation, and decision-making demonstrates that our chances of accomplishing a particular goal increases when we consider potential barriers, negatives, or possibilities that might lead to failure. The act of mental contrasting, where you look at both positive and negatives and try to develop a realistic picture, has shown to lead to better overall outcomes. The “never quit” ideology also fails to hold up to philosophical scrutiny. To promote a belief that failure is “unthinkable” eliminates the most powerful asset we have available, the power to think. If it is unthinkable to think about failure, then we are inadvertently severely limiting our chances of success. It is by allowing ourselves to think about failure, that gives rise to potential solutions, to options and ideas that might help us overcome certain obstacles. Therefore, what is truly unthinkable is to limit our thinking, to in effect stick our head in the sand, ignoring failure as a potential reality. (2) The abc's of deciding to give up.If we can agree that failure is sometimes an option, we can then move the discussion forward and ask ourselves under what conditions. When should you give up? Turning to research on goal achievement, economics, and decision-making, one way to determine when to give up revolves around answering three fundamental questions, (1) is the goal still desirable, (2) is it feasible, and (3) what other opportunities are available? a. Is the goal still desirable? A useful analogy is tunneling for precious gold, ore, or some other valuable commodity. As long as the commodity remains desirable, then we can justify continuing or efforts. If on the other hand the commodity drops in value, then while it might be entirely feasible to continue digging, committing additional labor is the wrong decision. b. Is the goal still feasible? Generally speaking as we progress towards a goal, achieving the desired outcome seems more and more within our grasp, i.e. more feasible. If we have already demonstrated it is feasible to dig 100 feet, then there is no reason to believe digging the final 6 inches is for some reason unfeasible. But, this is where we sometimes make a mistake. The past doesn’t necessarily prove the future. At any point, conditions may change, altering the degree to which achieving a particular goal is possible. Sticking with a mining analogy, there are any many things that can occur, from collapsed or flooded tunnels to broken equipment. c. What other opportunities exist? When we commit ourselves to a goal, sometimes we develop tunnel vision, where we get so focused in on a goal that we fail to consider what other ways we might use our time and resources. To some extent this tendency is a result of hardwired biases that favor avoiding pain over an equivalent gain. While these biases can help us to persist in our pursuits, they can also lead to issues like, sunk costs, escalation of commitment, and loss aversion. One way to lessen or overcome these kinds of bias is to take a step back and recalculate the desirability and feasibility of a current goal in comparison to other goals or potential opportunities. In terms of our miner, it means making sure to periodically leave the tunnel to help maintain a broader view of the world. (3) The power of purpose.There is science behind asking yourself the three questions related to desirability, feasibility, and opportunity. Namely, studies on goal achievement have identified that we tend to better recover from failure when goal disengagement is followed by a period of reflection and then goal reengagement. In other words, when we replace one goal with another, when we find new purpose to replace the former, both the intensity and duration of pain is lessened. And this ability to deal with failure, to learn, to recover, and to reengage cannot happen when we do ourselves a disservice and refuse to think about the unthinkable. References Hoffman, B. (2017). Hack your motivation: Over 50 science-based strategies to improve performance.

Klein, G. A. (2017). Sources of power: How people make decisions. Moskowitz, G. B., & Grant, H. (Eds.). (2009). The psychology of goals. Guilford press. Wrosch, C., Scheier, M. F., Miller, G. E., Schulz, R., & Carver, C. S. (2003). Adaptive self-regulation of unattainable goals: Goal disengagement, goal reengagement, and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(12), 1494-1508.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed