|

This is the final article in the series on how you can get the most out of using SMART goals. My previous articles discussed establishing goals that are Specific, Measurable, Actionable, and Relevant. Now I want to discuss the final concept, Time Bound. In the article I cover why it is important to include things such as action feedback loops, incentives for process, and the need to account for the psychological principle of the planning fallacy.

Action Feedback Loops A common issue I see when using SMART is failing to harness the time driven power of action feedback loops. If you want to stay motivated and on track, structuring your goals to provide feedback at the correct frequency, i.e. the correct time, is critical to success. Scientific research using both rats and humans has shown that we prefer smaller rewards more frequently than a larger reward that is delayed. Applied to goal setting, this means you want to ensure to establish intermediate time frames to provide the right frequency of feedback and help keep you on the right track in pursuit of a longer-term objective. As an example, take the specific goal to lose 10 pounds in 10 weeks. Do you weigh yourself once and then 10 weeks later weigh yourself again? Or do you weigh yourself twice a day or once a week? Feedback spread too far apart is unlikely to keep you motivated and feedback that is too frequent is not very useful, efficient or actionable. Establishing the correct frequency that works for you is important. You want the frequency to be often enough to give you useful information that is actionable. If you step on the scale once every two weeks, this will provide you actionable feedback about the extent to which your process is working. Speaking of Process and Rewards When you set up feedback based on time, it is not simply to decide “yes” or “no”, did you achieve your milestone or goal. Instead, time is a trigger to evaluate and adjust your process as needed. If after two weeks you have not lost any weight then maybe your process of going to the gym two days a week and eating less than 2,000 calories is not working. This evaluation based on the feedback loop you created allows you to adjust the process and try again. Maybe you need to go to the gym three days a week, try to cut back to 1800 calories a day or maybe you need a new action plan all together. After adjusting your process give it another two weeks and then evaluate again. Over time the adjustments will help you zero in on the process that works for you. Now this may sound a bit odd in a results oriented world, but I personally reward myself for process more so than outcomes. This does not mean I ignore outcomes, but that I choose to focus my recognition on process, because process is what drives results and that is where I want my motivation to originate, from an intrinsic desire to continuously improve my process. If two days a week at the gym and eating under 2,000 calories a day did not result in achieving my milestone of losing two pounds, my first question is did I follow my process? If the answer is yes, then while I may not be excited about the results I do not consider it a failure, rather a lesson in what doesn’t work. If on the other hand I failed to follow the process, then it is another issue all together and a topic for a different article. The Planning Fallacy Another aspect of Time bound, is learning to account for the well-established psychological principle called, the “Planning Fallacy”. Not understanding this principle can help set you up to fail, at least it will feel like failure when after 10 weeks you have not lost all the weight you had expected to lose. On the other hand, if you understand the planning fallacy you can take the results not so much as failure, rather as valuable information that you can use moving forward to make a more accurate estimate in the future. The planning fallacy was initially published by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in nineteen seventy-nine. What they discovered was the tendency for individuals to underestimate the amount of time and resources it will take to achieve their goals. In one study, college students were asked how long it would take them to finish a term paper. The average estimate was thirty-four days. They were also asked to provide an estimate if everything went horribly wrong as well as if everything went smoothly. The smooth scenario, where the grass is green and the skies are blue, resulted in an average of twenty-seven and a half days while the worst-case scenario, where a dog ate your homework; the average estimate was forty-eight and a half days. The interesting thing is that the average actual completion time was fifty-five and a half days, well above even the worst-case scenario. With further studies they found that whether it is an individual prediction or a team effort, the planning fallacy results in project overruns and missed deadlines. A well-known example is the Sydney Opera house, initially scheduled to open in 1963. It took ten years longer than estimated, opening a scaled-down version for roughly 15x the original estimated costs. How could those involved in the project been so bad at planning? Why You Can’t Plan There are a number of theories as to the psychological reasons we are so bad at estimating into the future. One of the more popular theories is that when we recall our past performance, any delays we experienced, we tend to attribute those delays to external factors that were beyond our control, while discounting any factors related to our personal performance. Another theory is that when making future predictions, it is difficult to estimate the cumulative factor of small, individual distractions and mishaps that will occur, such as an unexpected phone call. Instead, we only look at the major elements we believe we can control and build future predictions based on this ideal scenario. So what can you do to deal with the planning fallacy? The number one way technique is to make sure that you anchor any future predictions based on your actual past performance. This means to avoid substantially altering predictions without having a very good reason to expect different results. It does not mean to ignore projected changes or benefits of a new idea, method or process, but just to make sure that any predictions of improvement or growth are firmly rooted on the foundation of your past results. The Bottom Line When it comes to establishing SMART goals, you want to harness the power of time by making sure that your goals are Time Bound. This means making sure that you consider things such as;

To put it all together, the SMART format is a structured method to goal setting that provides an evidence-based approach to achieving your goals. While it is not the panacea for all of the challenges we face in life, if you have read all of the articles, it is another tool that you can now place on your metaphorical tool belt. You now have the means to use SMART as a way to establish and monitor goals that are specific, measurable, actionable, relevant and time bound. If you have not read the other articles, you can use the following links: Specific Measurable Actionable Relevant If you have any questions or suggestions, please contact me at [email protected].

About the Author:

Richard Feenstra is one of the unfortunate individuals in life, cursed with getting just slightly better looking each day. By the time he is in his 90's he will be an international heart throb. During the meantime, Richard enjoys sharing what he has learned over the years about the art and science of decision-making. (Keywords: cognitive dissonance, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, goal setting, scaffolding, cognitive bias, judgment, bounded rationality, SMART goals, motivation, self-regulation, goal achievement.)

2 Comments

My last three articles have addressed SMART goals and structuring your goals to be Specific, Measurable and Actionable. In this article I am going to discuss the next aspect of SMART, which is to ensure that your goals are Relevant. I will explain why it is important and provide two techniques that you can use to make sure that at any given point in time you are pursuing those goals most relevant to your success.

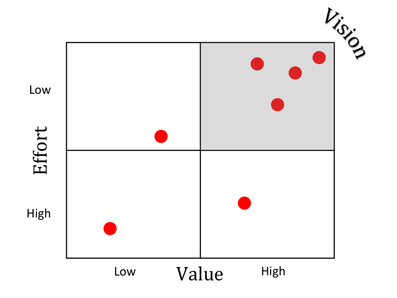

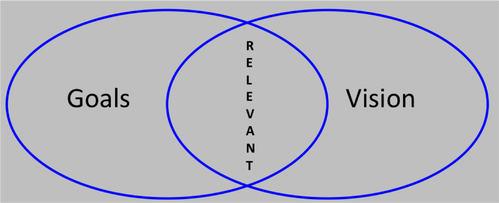

Why Relevant? Most versions of SMART do not use relevant. In my opinion those versions neglect two key aspects of goal setting, (1) that we all have more goals than the time we have available and (2) that goals are not strictly independent of one another. Versions of SMART that do not use relevant are silent on these issues, providing no guidance on how to evaluate multiple goals. Therefore, to get the most out of goal setting and improve your chances of success, you not only want to make sure your goals are aligned with your vision and your values, but you want to maximize your time and resources to pursue only those goals most relevant to your long-term success. Value and Effort One way to evaluate multiple goals is to place each goal relative to one another on a matrix that looks at perceived value verses effort. When you look across goals, you want to focus your resources pursuing those goals most relevant to your vision that are low effort and high value. To reinforce, the use of the matrix is a relative process. Hopefully any goal you are looking to achieve has a degree of challenge that will involve substantial effort. The method then, when ranking effort, is simply a comparison between competing goals. For instance, I have a goal to publish a book. Should I write a work of fiction that tells a story of an evil mastermind and his plans to conquer the world or should I write a book that explains 7 key psychological principles that you can use to harness the power of the human mind? Both would be a challenge to write, both will take significant effort, but given my values and my background as an educational psychologist, the book about the human mind will take less effort and have a higher value than the work of fiction. The Pareto Principle A second method for determining which goals are most relevant is to use the Pareto principle, also known as the eighty twenty rule. This takes all goals that are under consideration and asks which are the 20% of your goals that will provide 80% of your results. It is this top 20% that are the goals most relevant to your success. This does not mean to discard the remaining goals, simply to hold them in reserve as you pursue your most relevant goals. Periodically, as you accomplish a goal or new ideas present themselves you will want to revisit the Pareto Principle, dusting off old ideas to determine what to pursue next. And an additional use of the Pareto principle is to help manage your resources in pursuit of those most relevant goals. One option is to commit all of your time and energy to the 20% of your goals that are most relevant. However, another option provides a bit more flexibility, committing 80% of your time to the most relevant goals and 20% of your time to goals not necessarily aligned with your vision. The benefit of this arrangement is that it helps focus the majority of resources on the most relevant goals, yet leaves some room to experiment with new ideas. Maybe I can write my book about an evil mastermind after all, it may just take me a lot longer to complete. The Bottom Line If you are anything like me then your to-do-list expands as you pursue multiple goals in life. You have more ideas than hours in the day. But, every idea is not created equal so you need a mechanism to evaluate your ideas and establish those goals most relevant to your success. Two techniques to evaluate multiple goals are: -1- Use the Value/Effort Matrix: this will compare your goals along two criteria to help ensure you are focused on low effort, high value goals. -2- The Pareto Principle: this lists all your goals and then you select the 20% of goals that will give you 80% of your results. In my next article I will be discussing the last aspect of SMART goals, the importance of ensuring that your goals are Time bound.

About the Author

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist who at the age of only seventeen became an expert in throwing hand grenades. Richard enjoys sharing the psychology of decision-making with a vision to help transform the world, one decision at a time. This includes writing about scaffolding, cognitive dissonance, cognitive bias or other keywords he wanted to list here in a feeble attempt to influence search engines. |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed