For over 20-years a monthly tactical decision game (TDG) was published in the Marine Corps Gazette. These games allowed readers to play along by submitting their solution. In the next issue a discussion was published, presenting the back and forth dialogue that took place as players explained their rational and why they decided to take a particular action. From the military, the value of TDG’s has branched out into other fields of expertise. As a form of ‘problem-based learning’, a TDG can be used in sports, business, aviation, the 1st responder community, or any profession that routinely needs to make high stakes decisions under time pressure. In this article, the basics of creating and playing a TDG are presented. In addition, the article suggests two ways to improve a TDG by incorporating elements of Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM). Last, you can learn more about TDG's by downloading a free copy of “Mastering Tactics - A Tactical Decisions Game Workbook”, by Maj John F. Schmitt, USMCR. What is A Tactical Decision Game? A tactic is an action intended to produce an immediate result. For example, a soldier decides to flank the enemy to gain advantage, a medic applies a tourniquet to stop a patient from bleeding, a firefighter clears brush to deprive a fire of fuel, or a bicyclist stays behind the leader of a race in order to reduce drag and conserve energy. In most professions, and life in general, there are any number of tactics we repeatedly use and then there are tactics that we might consider, or prepare to use, but the situations requiring such tactics are less common or even rare. For instance, a medic may never need apply a tourniquet, and you may never need to decide how you will respond to a fire in your home. Still, in both cases it is a good idea to consider the possibility. And this is where the game aspect enters the equation. It is a hypothetical “What if” scenario that allows players to develop a plan of action and discuss potential outcomes. In this sense, a tactical decision game is a mental simulation of how to respond to a situation before it actually occurs. WHY PLAY TDG’s?The main purpose of a TDG is to help you make better decisions, to accelerate your expertise. It is to broaden your experience, exposing you to a broad range of situations that you may encounter. And even if you don’t encounter the exact situation, the act of simulating various possibilities can provide insights that might help across any number of variations.  A good way to explain how TDG’s promote expertise is to consider research on chess. When a novice player first starts to play chess they only know the basic rules. They have zero experience, which means they cannot yet recognize common patterns. As the novice gains experience they begin to see familiar situations and through trial and error develop tactics and counter tactics to improve their decisions. And even though rarely will two games ever be exactly the same, there is enough recognition of recurring patterns that the player gains in skill, moving from novice to intermediate. But playing chess is not the only way to gain experience. To the extent a player has a passion for chess and wants to pursue expertise they can accelerate their learning by playing TDG’s. This might take the form of studying the play of Grandmasters, or of historically tough games and mentally simulating potential moves. While the player will most likely never find themself in that specific situation, the “What if” provides the player the opportunity to gain insights that can be applied to similar scenarios. Another way to frame the discussion is to consider research by Dr. Gary Klein that found developing expertise is less about any given amount of time and more about the breadth of experiences. In his work he found even though rural and urban firefighters may have the same years on the job, the urban firefighters had typically responded to a wider range of calls, allowing them more opportunities to develop their expertise. Besides improving decision skills and developing expertise, there are a number of other benefits to using TDG’s.

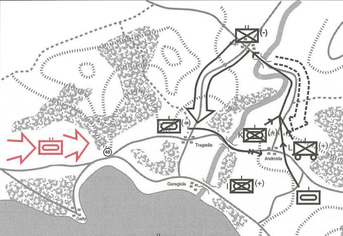

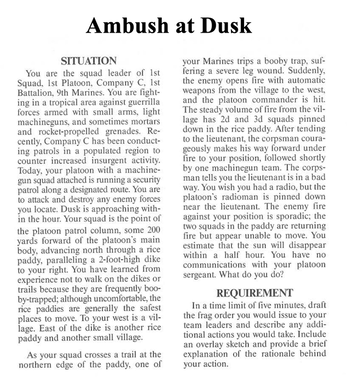

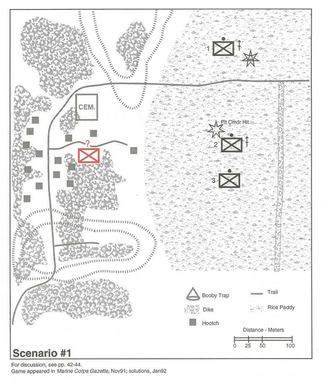

How To Create a TDG There are three elements to creating a solid TDG; the situation, supporting materials, and requirements for play. As an example, Ambush at Dusk is an actual TDG created by John Schmitt for the military. The Situation Fundamental to a good TDG is creating a situation that presents players with the need to solve a problem through immediate action. The creator should adopt the perspective of the decision maker, of the player, and briefly describe the Who, What, When, Where, and Why of the situation. For instance, in Ambush at Dusk you are the squad leader. You find yourself in a rice paddy with your platoon receiving fire from the direction of a nearby village. The situation you create can be purely hypothetical or it can be based on a historical example. For instance, Ambush at Dusk is based on a battle that occurred in Vietnam. And while that situation took place over half a century ago, there is still plenty of value for soldiers in modern armies to consider how they might respond should they encounter similar conditions.  Supporting Materials In addition to describing the situation, you may want to include any materials that the players might reasonably have access to or use under actual conditions in support of the decisions they make. For the military, the use of geography, maps, or visuals is a common way to try and make sense of a situation as well as communicate intent. Soldiers visualize the terrain and relative positions of units. For other domains supporting material might be patient records, weather or radar maps, stock charts, or audio recordings. In Ambush at Dark the players are provided a graphic of the general situation through the eyes of the squad leader. Requirements The third element of a TDG is to provide the players with specific requirements for providing their solution. This includes a time limit and a method to communicate. The time limit should be short enough to create some friction or stress, while long enough to allow the player sufficient time to reasonably communicate their actions. In Ambush at Dark the players are given 5-minutes to communicate their solutions using a frag order, which is an established way to relay orders during combat. The players are also told to provide an overlay, indicating how their solution would unfold on the map, i.e. on the battlefield. How To Play a TDGAfter creating the game it is time to play. This involves gathering a few players, explaining the rules, going through the scenario, and then hosting a discussion. While there is no set time limit, a typical TDG with a handful of players can be completed within an hour. The Rules Technically any rule is not strictly necessary. In this sense they might be considered guidelines. A word of caution, however, is that over several decades of playing TDG’s the following rules have proved useful:

Going Through the Scenario While there are several ways to play a TDG, including solitaire and double-blind, the most common way is group play. This involves establishing a time to play, inviting a number of players, and then one person hosts and/or moderates the session. A process the moderator can use includes:

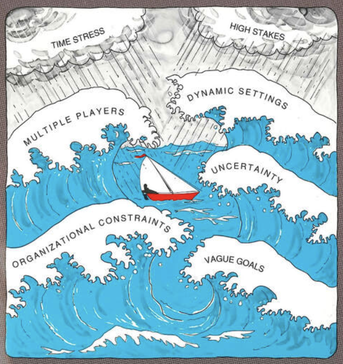

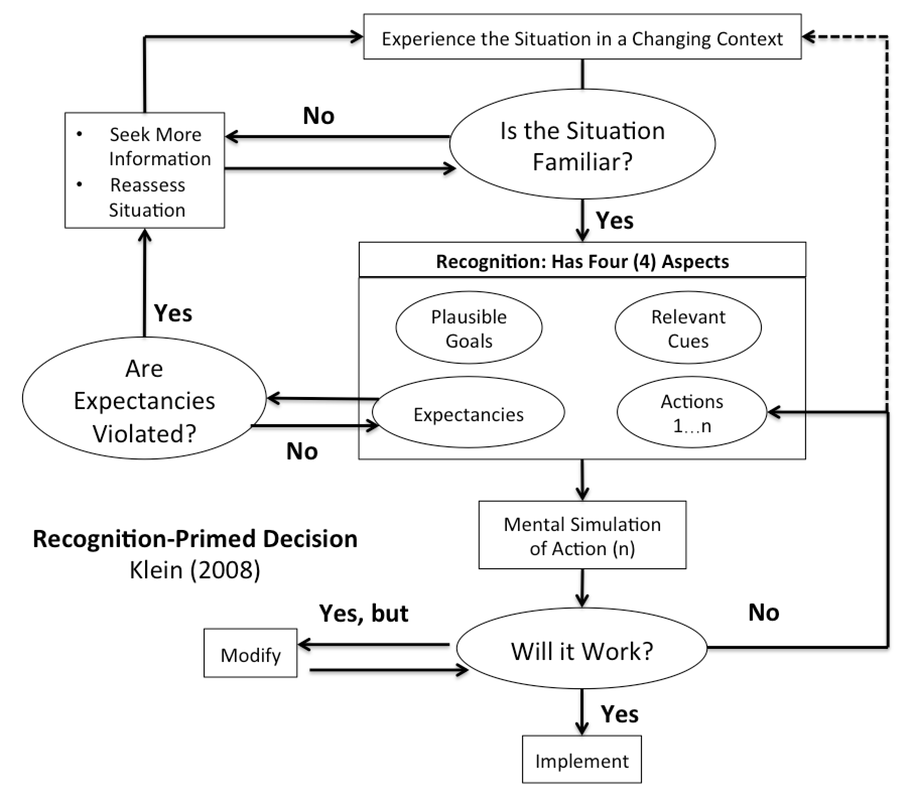

Hosting the Discussion The real value of a TDG is in the discussion that is held after players have presented their solutions. It is at this point that the moderator’s role is to prompt players to explain the rational behind their actions. Players can then discuss various aspects of the scenario, including any perceived strengths or weaknesses of a given solution. This includes being able to prompt the players to discuss “What if” questions. What if this or that would have happened, then what? In this sense, the discussion becomes a collaborative effort to gain insights and develop a shared mindset. In hosting a discussion, the moderator should try to ensure that all players get the opportunity to express their opinions. It is important to avoid only one or two players discussing their ideas while others do not engage. TWO WAYS to Incorporate NDM Decision Making in Action: Models and Methods Decision Making in Action: Models and Methods Naturalistic Decision Making (NDM) is an approach that looks at how individuals make decisions under real world conditions. This is in contrast to rational or economic models that approach decision making as a phased or linear process under controlled conditions where the “correct” answer is predetermined. In both the creation and play of TDG’s, there are at least two ways to incorporate research from the NDM community. One is to include NDM conditions in the design of the game. The second, is to use the recognition primed decision (RPD) model when hosting a discussion. NDM Conditions Among other things, real world conditions often include time stress, high stakes, multiple players, dynamic conditions, uncertainty, organizational norms, and vague goals. Another factor that is difficult if not impossible to replicate using rational models is the impact of experience. This includes both declarative and tacit knowledge, as well as the insights gained by individuals as they continue to engage in a given domain. When designing a TDG, consider to what extent the situation you have created includes the above real world conditions. If, for instance, your situation has a clear goal and a single definitive solution, it might not be a good candidate for a TDG. The RPD Model Besides the value of “What if” questions, consider using some aspects of the RPD model to prompt further discussion. When hosting a discussion, hand out a copy of the model and when appropriate ask:

For a 3-minute video explaining the RPD Model click here Why incorporate NDM?Unlike rational models that determine an optimal or “correct” answer, a naturalistic approach most often looks for a solution that is “workable” in the moment. In this sense, NDM is better aligned with tactical decisions, in that a solution does not need to be ideal. Instead, there is an acknowledgement that real world situations are complex with multiple potential solutions. The bottom line is that incorporating elements of NDM will improve the overall game. A TDG will come across as more realistic and therefore will be more engaging. In addition, using NDM conditions and the RPD model will begin to introduce players to a common language when discussing scenarios. And if TDG’s are played on a regular basis, you can expect the language of NDM to transfer to discussions about actual events. Players will be able to discuss real issues in terms of time pressure, uncertain conditions, sensemaking, goals, cues, potential actions, etc. Final ThoughtsWhile there is probably no substitute for actual experience, we can endeavor to improve our decision making skills through simulation. While computers or full scale live simulations are arguably more realistic, they come with costs that are often prohibitive in both time and resources. TDG’s on the other hand offer a low cost, flexible alternative. To create and host a TDG is fairly straight forward. It can be accomplished in only a few hours. All that is needed is to develop a situation, establish requirements, and furnish any supporting material. After players provide their solutions a collaborative discussion is moderated, allowing everyone to participate and gain insights from the other players. For added realism, consider incorporating elements of NDM into your games. While not a required part of a TDG, using an NDM approach can make the simulations better aligned with the nature of tactical decisions as well as have long term benefits, introducing a common language for understanding how we make better decisions. Scroll to the bottom if you are interested in John Schmitt's "Mastering Tactics" Workbook.  A Tactical Decision Games Workbook, by John Schmitt. Download here.

1 Comment

5/24/2022 05:29:30 am

What an exquisite article! Your post is very helpful right now. Thank you for sharing this informative one.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed