|

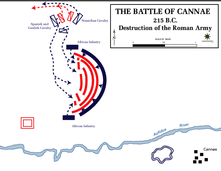

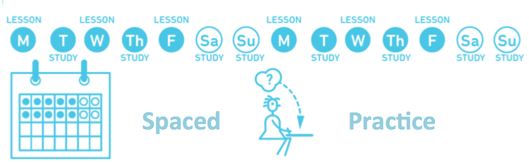

Whether you or someone you know is headed back to school or you have set a goal that involves learning, like speaking a foreign language, there is a wide range of strategies you can use that will help you to learn more efficiently, maximizing your time and effort. In this article I want to share with you 7 of these strategies, backed up by scientific evidence. Strategy One: Spaced (Distributed) Practice You can boost your ability to retain information by scheduling several small study sessions, spacing them out over time. This has proven more effective than the age-old practice of “cramming.” To get the most out of spaced practice, make study sessions shorter and give yourself plenty of time between sessions. Instead of a single five (5) hour marathon session, break it down into one (1) hour sessions that take place over several days or a week. If you are studying multiple subjects, break it up so that you are rotating between subjects. The reason spaced practice is so effective is that it helps you to focus on the more important concepts, prompts the need to recall from previous sessions, and limits the time available to become distracted by irrelevant material. The most challenging aspect of spaced practice is having the discipline to create a schedule and then following through. If you find it difficult to stick to your schedule, consider adjusting the frequency or take a look at your overall workload.  Strategy Two: Concrete Examples Learning has proven more effective when a person learns in context, being able to visualize how they can apply what they are studying in the real world. This can be more or less difficult dependent on the extent to which a person can attach what they are learning to a concrete example. There are primarily three ways to take learning from the abstract to the applied:

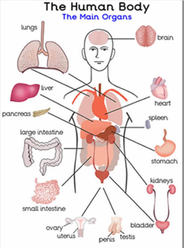

Regardless of how you connect what you are learning to a real world application, the thing to remember is to try and attach it to a concrete example. Getting people involved by providing a concrete example helps both in understanding and retrieval of the material. “Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.” – Benjamin Franklin  Strategy Three: Dual Coding Have you ever heard that pictures are worth 1,000 words? With the explosion of the Internet more and more research is proving that combining words with visuals helps people better retain information. The process of using text with visuals is called dual coding and it can come in a variety of forms:

For example, if you are trying to learn anatomy, such as the kidneys, liver, lungs, heart, and brain, then having a diagram of the human body can help over using flash cards that only contain text. According to research, pictures are processed 60,000 times faster than text and visuals are processed using an area in the brain associated with long-term memory, while text uses working or short-term memory. When using dual coding, start by initially connecting text with a visual reference and work your way up to more advanced techniques, drawing the visual from memory. This is can be especially useful in multi-media learning. Strategy Four: Elaboration This strategy asks how or why something works in a certain way. From the original question you begin to dig deeper, searching for additional resources and materials that can help provide answers. The process of elaborating helps you build a better understanding. When using elaboration it can help to compare and contrast opposing ideas. You may want to seek out opinions and have discussions with friends or colleagues. In a technology rich environment you can use the Internet to access previous research on the subject. When using elaboration, there are at least two things to keep in mind:

Strategy Five: Interleaving This strategy works great in conjunction with spaced practice. Interleaving is the intentional switching and rearranging of topics during a study session. Study one topic or subject for a short period of time and then switch. Interleaving is best used when topics have some crossover or similarities. For instance, when studying to learn a foreign language you may (a) read a short story, (b) memorize new vocabulary, (c) practice conjugating verbs, (d) have a practice conversation, etc. In a study session you may want to split up a long session into a,b,c, then d,c,a, then b,d,a. By mixing up the topics and switching periodically it will help you to make connections between the material and gain a better overall understanding. Be careful not switch between topics too often. A good rule of thumb is to spend at least 45 minutes, but it really depends on what you are trying to learn. Interleaving can also be used with subjects that have limited crossover, such as studying biology and then economics. While making connections between diverse subjects is not likely, switching gears can help promote critical thinking skills. Strategy Six: Retrieval Practice This is a great strategy to begin a study session, by first reviewing any previous material. In Robert Gagne’s, 9 events of instruction, stimulating the recall of prior material is an important aspect of helping to learn new material. The best way to use retrieval practice is to leave all of your books and materials from a previous study session closed. Take out a pen and paper and either create a list or draw as much as you can remember. For instance if you are studying anatomy you might be able to draw a body and place organs in roughly the correct locations, even if the names of the organs escape your memory. Another way to practice retrieval is by using flashcards or quizzes. Dependent on what you are trying to learn the material may already come with some pre-made tests. If you are studying with a friend, you can take a few minutes to quiz each other on the main concepts or ideas. Strategy Seven: Gamification The last strategy you can use to help improve your learning is called gamification. This is where you take the material you want to learn and use different techniques to turn the lessons into a form of game. This can be combined with other learning strategies to help boost motivation. For instance, if you have decided to use retrieval practice, instead of a simple quiz, you might decide to create a home version of the popular television game show, “Jeopardy”. More advanced forms of gamification use the learning objectives and materials to provide various incentives, such as leveling up, badges, unlocking rewards or in some cases imposing some form of penalty. Gamification taps into the affective components of learning. A person can become more motivated to learn if they feel a sense of accomplishment as they level up. Conversely, some types of gamification harnesses loss aversion, the psychological fear of losing a reward previously gained. There is a balance when using this strategy to make sure you are not too distracted by the game, in lieu of actually learning the content. I remember playing Oregon Trail, a game designed to teach about settlers crossing the American West. One aspect of the game allowed for hunting, which became a distraction over learning concepts more central to that time in U.S. history. Summary

Whenever you set a goal that involves learning, consider using strategies that can help you maximize your effort. There is no reason for you to pursue any serious goal without taking some time to develop a solid plan to help you achieve your goal in less time or using fewer resources. I want to take a moment to credit learningscientists.org for this article. Six of the seven strategies discussed in this article have free posters that you can download here, for free. References Benjamin, A. S., & Tullis, J. (2010). What makes distributed practice effective? Cognitive Psychology, 61, 228-247. Mayer, R. E., & Anderson, R. B. (1992). The instructive animation: Helping students build connections between words and pictures in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 4, 444-452. McDaniel, M. A., & Donnelly, C. M. (1996). Learning with analogy and elaborative interrogation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 508-519. Rawson, K. A., Thomas, R. C., & Jacoby, L. L. (2014). The power of examples: Illustrative examples enhance conceptual learning of declarative concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 27, 483-504. Roediger, H. L., Putnam, A. L., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational practice. In J. Mestre & B. Ross (Eds.), Psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education, (pp. 1-36). Oxford: Elsevier. Rohrer, D. (2012). Interleaving helps students distinguish among similar concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 355-367. Wong, B. Y. L. (1985). Self-questioning instructional research: A review. Review of Educational Research, 55, 227-268.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed