|

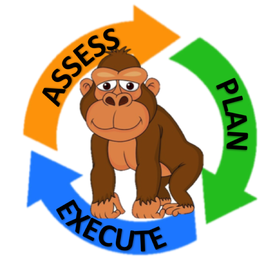

Have you ever had to justify a decision? Have you ever looked back at a decision and wondered what went wrong or how you might improve? Each of us, whether for legal, professional, or personal reasons, have at some point faced these questions. And while many times you might have been able to provide a clear answer, most certainly there were times when you were less than certain. This is where A.P.E. can help, a decision tool that uses a straightforward, three-step model of; assess, plan, and execute, to break down the decision process. Assess, Plan, Execute As a general model, A.P.E. is a cyclical process that spans both time and scope. We assess the situation, develop a plan, and then execute. These are the three (3) key elements of any decision, and therefore are fundamental to the underlying process of making a decision. A.P.E. is a model that can be used to describe the process of making a rapid, high stakes decision in a dynamic, uncertain environment, yet is equally capable of allowing us to understand how a decision is made under stable conditions that are low stakes, static, and certain. Given this flexibility, the primary value of A.P.E. is that regardless of context we can use it as a tool to analyze past decisions or deliberate on future decisions. We can also look at outcomes, whether potential or realized, and use A.P.E. to help dissect the key components that make up the decision process. Of equal value is the ability to use A.P.E. as a common language across decision scenarios. This makes A.P.E. a useful way to communicate, regardless whether we are discussing a decision to build a new trauma center or we are discussing a split second decision to perform emergency surgery. It allows the same language to be used in order to discuss a high-level policy decision, yet communicate how we might best apply that policy under real world conditions. Assess

Being a continuous cycle, we begin this short discussion with the concept of making ongoing assessments. This includes monitoring of both the external and the internal, of both the physical world and our mental sandbox. This occurs even while we sleep to lesser or greater degrees of awareness. In a state of deep sleep we are rather oblivious, while in lighter phases a noise or bump in the night rouses us from our slumber. Assessment includes concepts such as situational awareness and sensemaking, whether passive or active. It also includes the idea of intuitive, informal assessments as well as rational, labored analysis. Using human action and goal theory, assessment involves determining the extent to which there are gaps between our current state and some desired future state. Assessment helps establish what gaps exist, how large the gap, and which gap or gaps deserve the bulk of our time and resources, i.e. where we should focus. Plan Given our assessment, the next step is to plan a potential course of action to close any gaps. From the simple to the complex, developing a plan is highly dependent on the situation and the perceived time to act. In a very dynamic environment where the stakes are high and time is limited, plans will most likely involve basic pattern recognition and sequential evaluation, moving on to execution as soon as the first workable or “good enough” plan is determined. In a less dynamic environment, where time is sufficient, planning can involve the development and evaluation of multiple concurrent options, including goals and sub-goals. Execute With our plan, the final part of the process is to actually execute. This involves taking the plan out of our heads, off the drawing board, and taking concrete steps to turn the plan into reality. This includes implementation, monitoring feedback, making adjustments, and evaluating outcomes. A good example is repeated throws to hit a bull’s eye with a dart. The assessment and plan are relatively static, while we monitor and adjust dart after dart. Another example would be an after action review, where the focus is on lessons learned. Reassess As an ongoing cycle, execution then blends back into assessment. Unless we become fixated or experience a form of ‘tunnel vision’ or ‘cognitive lockup’, we are most often not oblivious to the world around us. Using a dual state theory of mind, during execution we are both focused on feedback related to goal progress, but also are continuously updating the overall situation. In a state of continuous sensemaking, we periodically pause actions related to execution, taking some time to reflect and reassess. Application: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly There are basically three outcomes whenever we make a decision. There are outcomes we consider clearly good, there are outcomes we consider clearly bad, and then there are the ugly decisions where we just throw up our hands because we just aren’t sure what to think. In every case, A.P.E. is a tool that is a form of cognitive task analysis (CTA) that can help us better understand and ultimately improve our decision-making ability. The Good One thing I like about the work of psychologist Gary Klein is that he focuses on how first responders and similar professions make great decisions under time stress and less than ideal conditions. I don’t think we do that often enough. It seems like that the vast majority of the time we wait for a bad outcome and then try to figure out what went wrong. Klein does pretty much the opposite. His work takes good outcomes and applies CTA to figure out how we can repeat them, improve upon them, and share them. In this way, a novice nurse or firefighter advances towards making expert level decisions at a much faster pace. The Bad There are outcomes that sometimes are clearly bad, e.g. a plane crash. While a bad outcome doesn’t necessarily mean a bad decision was made, it is a common application of CTA. We want to be able to analyze our decisions in an effort to explain and prevent a similar bad outcome in the future. Using A.P.E. is a simple form of CTA that can help narrow in on what might have gone wrong. Was there an inaccurate assessment, was it a bad plan, or was there a failure to execute? Based on the findings, what do we need to adjust? The Ugly In my opinion the more fun application of A.P.E. is when we have uncertain outcomes. Most often forward focused, it looks at each phase of the decision process in an effort to predict or provide clarity to an expected outcome. In the reverse, an outcome is first assumed, and then A.P.E. is applied to develop decisions and potential courses of action. This is more a spy vs. spy or red team application, where CTA is used to get inside the mind and motives of a 3rd party. Figure out their A.P.E. cycle and then counter with your own. Upgrading to Advanced A.P.E. Given the various ways A.P.E. can be applied, adding it to your cognitive tool belt doesn’t cost much. In fact, the basic version is free. It comes pre-installed as a hardwired feature of being human. From the time you get up until you go to sleep, you continuously assess, plan, and execute. As long as things run smoothly, you don’t even notice A.P.E. working in the background. This is the basic, more intuitive side of our natural ability to decide. To then go from basic to advanced, requires us to actively consider the good, the bad, and the ugly. It requires formal consideration of each phase of the decision process. By doing so, it can help you to justify, explain, and learn how to improve your decision-making ability. Give it a try. References Crandall, B., Klein, G. A., & Hoffman, R. R. (2006). Working minds: A practitioner's guide to cognitive task analysis. Mit Press. Klein, G. (2008). Naturalistic decision making. Human factors, 50(3), 456-460. van den Heuvel, C., Alison, L., & Power, N. (2014). Coping with uncertainty: Police strategies for resilient decision-making and action implementation. Cognition, Technology & Work, 16(1), 25-45. keywords: decision-making, judgment, cognitive task analysis

2 Comments

We humans are error-prone creatures. So, mistakes can happen. The best thing is, you just need to justify your bad decision. A person usually feels uneasy when he has two conflicting ideas. It is described by the term cognitive dissonance. It happens to everyone all the time. However, through a confirmation bias, a proper justification can be made. You need to admit your mistakes in order to learn and to grow. Admitting an error can come handy in all situations. Justify your choices and strive for simplicity to make an unstoppable growth in this competitive world.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed