In this article I am going to discuss the science of regret. Specifically, I want to focus on regret as a cognitive skill that you can develop, as a tool that you can use to improve decision-making by regulating the intensity.

The Science

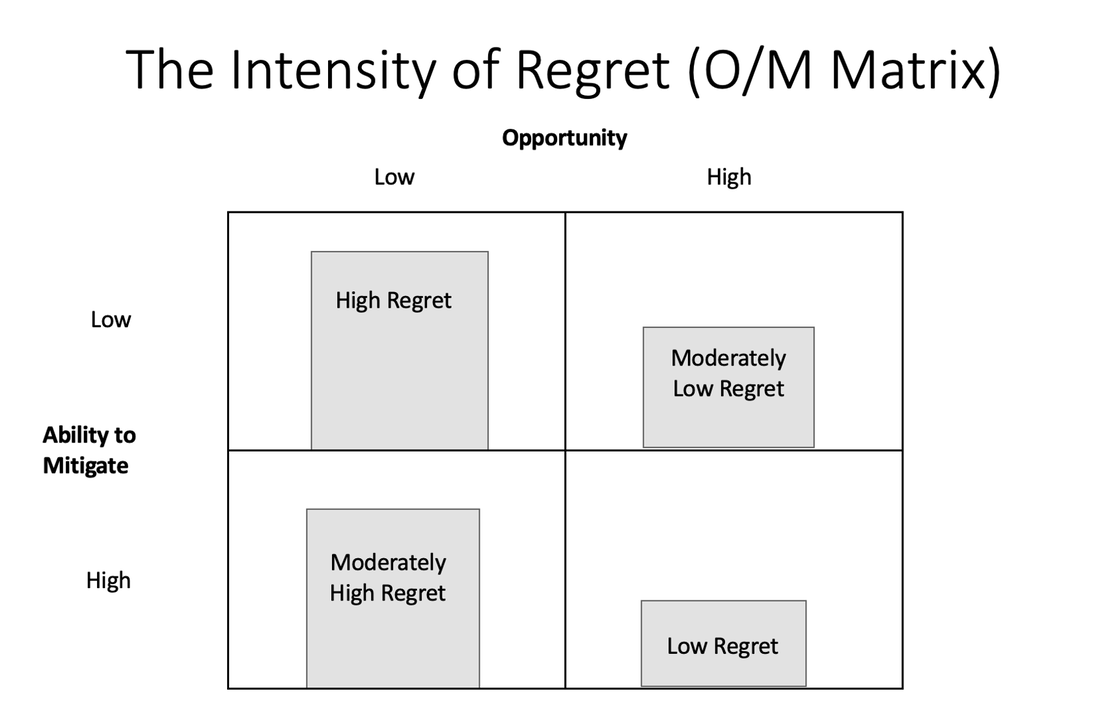

The Purpose of RegretPain, whether physical or emotional, often times serves an evolutionary or adaptive purpose. Unlike some theories of the rational, cold, economic decision-maker (Homo economicus), research supports that we (Homo sapiens) are adaptive decision-makers. In this sense, a certain degree of pain is often times functional, if not for the individual at least for the group. When it comes to the emotion of regret studies show that it can help to modify future decisions. Seven Ways to Harness RegretGiven our current understanding, what are some ways that you might you use regret? Researchers often refer to ways we might better “regulate regret”, implying that the goal is not necessarily to eliminate the pain. In other words, like a thermometer, there is an intensity or range of regret that can be healthy or productive. It is therefore not a matter of avoiding the emotion, but rather harnessing it to help you make better decisions. That said, the strategies we use to regulate regret are usually focused on ways we can reduce the intensity, including:

Final ThoughtsTaken together, you can use the strategies listed to try and balance the pain of regret with the ability to learn from your mistakes. To make better decisions, then, your aim should not be to mitigate or otherwise eliminate the pain. If you regret nothing, then in theory you will be setting yourself up to repeat the same decisions, to repeat the same mistakes. You will fail to learn. Instead, the goal in using these strategies is to harness regret, to use regret as a useful tool in learning how to make better decisions. Select ReferencesConnolly, T., & Zeelenberg, M. (2002). Regret in decision making. Current directions in psychological science, 11(6), 212-216.

Eryilmaz, H., Van De Ville, D., Schwartz, S., & Vuilleumier, P. (2014). Lasting impact of regret and gratification on resting brain activity and its relation to depressive traits. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(23), 7825-7835. Markman, K. D., & Beike, D. R. (2012). Regret, consistency, and choice: An opportunity x mitigation framework. O'Connor, E., McCormack, T., & Feeney, A. (2014). Do children who experience regret make better decisions? A developmental study of the behavioral consequences of regret. Child Development, 85(5), 1995-2010. Saez, I., Lin, J., Stolk, A., Chang, E., Parvizi, J., Schalk, G., ... & Hsu, M. (2018). Encoding of multiple reward-related computations in transient and sustained high-frequency activity in human OFC. Current Biology, 28(18), 2889-2899. Walster, G. W., & Walster, E. (1970). Choice between negative alternatives: Dissonance reduction or regret?. Psychological Reports, 26(3), 995-1005. Zeelenberg, M., & Pieters, R. (2007). A theory of regret regulation 1.0. Journal of Consumer psychology, 17(1), 3-18.

3 Comments

Sanket

12/29/2020 02:01:48 am

Thanks for such information

Reply

Marc Sajabi

12/17/2021 05:13:25 pm

Very relevant and applicable to experiences we see around us. I love it as it is knowledge that can be applied immediately to oneself.

Reply

william johnson

7/9/2022 11:36:50 am

Start out on the Grant Writing Course and looked at the decisionsskills.com website. A good amount of powerful useful information for this particular time in my life. I will look to invest (or read additional information) or utilize these articles as they relate to my new career path

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed