|

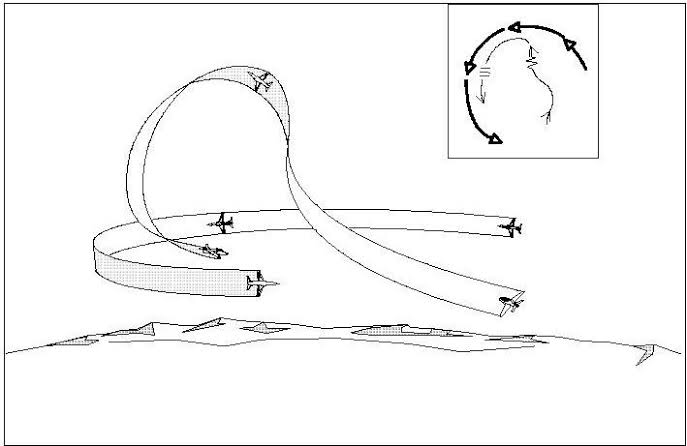

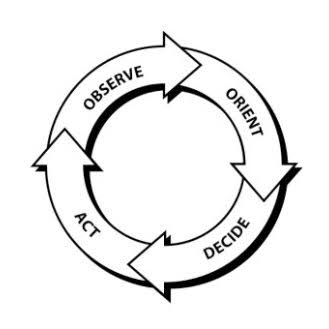

A 14 to 1 kill ratio. This was the number of Russian MIG’s estimated to have been shot down for every one American F-86 Sabre during the Korean War. While this estimate fluctuated, it was still this disparity that caught the eye of officer John Boyd, a fighter pilot in the United States Air Force (USAF). Boyd wanted to answer the question, “What makes the difference between winning and losing in competitive, high stakes environments?” In answering this question, Boyd developed a competitive decision-making model, ‘The OODA Loop’. While the model was initially applied to air combat, the OODA Loop quickly spread to other branches of the military and eventually made it’s way into any number of competitive or high stakes domains, such as sports, business, and the first responder community. The OODA Loop consists of four stages, (1) observe, (2) orient, (3) decide, and (4) act. Applied to air combat, prior to onboard radar, observe meant having good visibility, being first to see the enemy. Next, a pilot would orient, making sense of any observation, determining if it was a friend or foe, what position and how far away. Having gained “situational awareness”, the next phase was to decide what to do about the situation, to consider options. Do you climb, dive, turn into the threat or run away? The final phase is to then act on the decision, to test the hypothesis. This then updates the situation and takes the pilot back to observation.

ApplicationWhile never officially published, Boyd’s work became known as “The Green Book,” for the color of the paper used to print the 327 pages of slides titled “A Discourse on Winning and Losing.” It was this briefing that Boyd took to other branches of the military and eventually application found it’s way into other competitive domains. In each arena, Boyd’s model of decision-making can be applied both at the strategic and tactical level. Whether cycles are longer, like those typically found in command and control or executive board rooms, or extremely short cycles like those found in the field; pilots, firefighters, law enforcement, nurses, paramedics, or any profession that faces high stakes decisions under time pressure can benefit by improving whatever loops are critical to their area of expertise. Given such a broad scope, the main challenge then, is understanding how each phase of the cycle applies to you or your organization. What are you trying to accomplish or achieve? What are your goals? In terms Boyd would use, what or who is your enemy? What is the competition doing, how are they doing it, and to what extent can you get inside their loops or disrupt them? Applying the model then, requires taking each phase of the cycle and making it specific to whatever competitive challenges you might be facing in your field of expertise or area of interest.

ORIENT While observe comes prior to orient in the model, orient is by far the phase that has the greatest impact on our ability to win. How we are oriented influences what can be observed. Our current orientation frames and limits our observations. Described as the collection of past experiences and accumulated knowledge, we can only orient or make sense of things through a known frame of reference. This is sensemaking or using what we observe to gain situational awareness. And given that how we interpret what we observe is based on how we are oriented, i.e. on previous decisions and actions, on past experiences, this then has a significant influence on future decisions. Orientation then, is the phase of the cycle which represents the reservoir of all the knowledge you possess. It is from this position in the cycle that we define what we want to observe or what we can observe, and this then limits or defines the range of decisions we might take. Before moving on to discuss the decision phase of the cycle, it is important to note that both observe and orient are most often seen as implicit or intuitive processes operating for the most part subconsciously. Once it is learned that black dots in the sky are critical to survival and therefore relevant data, any future observation and orientation to black dots becomes automatic. The same can be said for any of our senses, in that once particular data is deemed relevant, then observation and orientation is most often not volitional, but an intuitive judgment based on pattern recognition, based on past experiences. DECIDE (Hypothesis) After we orient, the next phase of the cycle is to decide what action we want to take. This is seen as an explicit, volitional process of developing options or plausible goals. In extremely fast decision cycles, there is no time to consider all available options. Instead, options are evaluated sequentially with the first workable or “good enough” option being selected. In slower decision cycles options can be evaluated concurrently, trying to determine if option A is better than B is better than C or D, and so on. A way to imagine this concept is by using the game of chess. In the course of normal play there are no time constraints. Players can generally take as long as they wish to choose their next move, allowing them to compare and contrast as many options as they wish. This is representative of a long, slow decision cycle. However, in an alternate version of the game, ‘speed chess’, player have a finite amount of time to make a move, usually resulting in a very rapid back and forth with each player taking no more than a few seconds. Given such a fast cycle, players cannot evaluate all options concurrently and instead must defer to a sequential decision strategy, going with the first or second move that is deemed satisfactory. ACT The last phase of the cycle is to act on the decision. In this sense, the decision can be seen as a hypothesis and the action is the testing of that hypothesis. The decision comes with expectations of what should happen, and the action then confirms or refutes the decision as being productive in accomplishing the goal. In the simplest of terms the action is necessary to determine if the decision was “good” or “bad”. There are three considerations during this phase. First, there can be a significant delay between the action and observable results. For example, if the competition is an illness and the action involves medical treatment, there might be a delay of a few days to determine if the action was effective. Second, there is the case where the decision might have been good, but the action was executed poorly. To throw a dart at the bullseye to win the game might be an excellent decision, but poorly executed, the dart goes flying off in a less than desirable direction. Third, the situation might change, irrelevant of your action. This is especially true of longer decision cycles that take place in dynamic environments. This means that mid-action, the situation continues to evolve, possibly altering or even negating the effectiveness of the action. Regardless of the above considerations, action is what is intended to get inside of, or disrupt a competitors loop, allowing you to achieve your goal or in effect “win” the competition. Action is intended to modify the situation towards the goal you want to achieve. In this way, as the cycle continues and we return to observation, what you now see is an updated situation. LimitationsThe OODA Loop is not without criticism. Like any decision model, it is only a representation of how we make decisions and therefore there exists ample room to point out areas where the model does not reflect reality. Common criticisms include;

Next StepsDrawing on his experiences as a fighter pilot, John Boyd created the OODA Loop in an effort to explain what makes the difference between winning and losing in competitive environments. Regardless of any criticisms, Boyd’s work has arguably made an impact in any number of domains where high stakes decisions are being made under time pressure. His concepts are applied to this day and undoubtedly OODA loops will continue to be discussed for another generation. Taking into account the possible limits of OODA loops, the next step then, is to figure out to what extent OODA loops can work for you. In this sense, OODA becomes a new tool to add to your metaphorical decision-making tool belt. And like any tool, it is then a matter of selecting the right tool for the right job. The question, what competitive or high stakes situations are you facing? What are your current goals, what situations are you currently facing that may be competitive in nature, situations where you would rather win than lose? Identify one or two and begin to apply the model. Determine how you might improve each phase, how you might improve both the speed and quality of the decisions as to “get inside of” or disrupt the competition. ReferencesBoyd, J. (1987). A discourse on winning and losing. Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: Air University Library Document No. M-U 43947 (Briefing slides)

Brehmer, B. (2000). Dynamic decision making in command and control. In C. McCann & R. Pigeau (Eds.), The human in command. New York: Kluwer. Brehmer, B. (2005). The dynamic OODA loop: Amalgamating Boyd’s OODA loop and the dynamic decision loop. Hammond, G. T. (2001). The mind of war. John Boyd and American Security. Washington: Smithsonian Press.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed