Hard wired into our mental DNA is the need to reciprocate. When we receive a gift, the regions of the brain associated with emotion and decision-making light up. Studies on the social and psychological aspects of this activity show that receiving the gift triggers a cognitive dilemma that must be resolved. The easiest way to resolve the conflict is to give something in return of equal or greater value. In psychology this is known as the theory of reciprocity or social reciprocity. The Science The "Coca-cola" experiment is probably the most well known study on reciprocity. It was published in 1971 by Dennis Regan. In the study, the participant believed they were there to evaluate paintings. Also in the room was a fellow participant named Joe, but Joe was really Regan's assistant. First, Regan manipulated the degree to which a participant liked Joe, by having the subject overhear Joe being either polite or rude to a person during a phone conversation. In one condition, Joe would leave and bring back two soft drinks, giving one as a gift to the participant. In another condition, Joe would leave and return empty handed. After evaluating some art, Joe was then left alone with the participant at which point he would hand them a note, asking them to buy some raffle tickets. The results of the study showed the power of giving. In the condition where Joe did not give the participant a soda, the degree to which they liked Joe influenced how many raffle tickets they would buy. But, in the condition where Joe did give a soda, participants bought twice as many tickets as the no soda condition, regardless of the degree to which they liked Joe. So not only did people that did not like Joe buy tickets at twice the rate, they end up buying more raffle tickets than the cost of the soda. Application Since the "Coca-cola" study there have been numerous experiments that confirm that when you give, you shall receive. This is great if you are giving in a principled manner, but this is where the slippery slope of ethics enters the equation. Marketers use the principle to generate revenue. When you receive a letter in the mail asking for donations, it often comes with something for free. Years ago it was a small packet of stamps or address labels. Recently, I received a letter from a non-profit organization that contained a brand new, crisp, one dollar bill. At a shopping mall if you go near the food court there is almost always someone handing out free bites of their most popular items. Go to a trade show and you will walk away with a bag full of "freebies" or "swag". Surf the Internet and inevitably you will be offered a free newsletter, samples, or a free trial. It is up to you to decide where to draw the ethical line, how exactly you want to use this tool in influencing others to help achieve your goals. Personally, don't send me a crisp dollar bill, I know you don't really care about me and I see it as intentional manipulation. On the other hand, keep the free samples coming in the food court. I think you believe in your product and just want to offer me a tasty treat that might just convince me to take a seat. References Kawai, N., Yasue, M., Banno, T., & Ichinohe, N. (2014). Marmoset monkeys evaluate third-party reciprocity. Biology letters, 10(5), 20140058. Regan, D. T. (1971). Effects of a favor and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7(6), 627-639. Sakaiya, S., Shiraito, Y., Kato, J., Ide, H., Okada, K., Takano, K., & Kansaku, K. (2013). Neural correlate of human reciprocity in social interactions. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7, 239. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00239

0 Comments

Being motivated short-term is common.

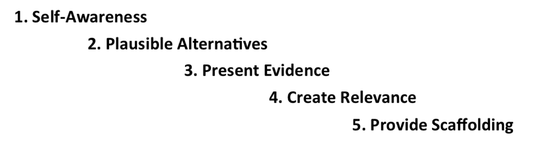

Having woken up after a night of heavy drinking or other debauchery, more than once I have said the words, “Never again.” And while one might think my motivation to avoid a recurrence of a night of regret should be high, research on lasting motivational change proves otherwise. As it turns out, good intentions are not enough to create and sustain enduring motivational change. It is not all about debauchery. Whether it is a goal you have set, a resolution you want to maintain, or a habit you want to establish, Dr. Bobby Hoffman has developed an evidence based five-step method for motivational change I want to share. This method can be used to help create lasting change for yourself or others. Step 1: Raise Self-Awareness Before any real change can occur you first have to be self-aware. This requires deliberate effort to raise your awareness as opposed to the concept of waiting until one hits the proverbial, “rock bottom.” Raising your self-awareness can be accomplished by creating a conflict. This means finding dissatisfaction or establishing disequilibrium with the current state. The goal is to maintain a level of cognitive dissonance that provides motivation to look for an alternative. A tactic I use for creating conflict is a journal I keep which forces me to reflect. Cemented on digital pages, I have a way to document both my struggles and successes. Periodic review helps raise my self-awareness, challenging me to search for ways to improve. Step 2: Present Plausible Alternatives Once you recognize things are not working out as intended, the next step is to develop plausible alternatives. What options are available? The best alternatives are those that can help you completely reframe the issue. The root cause of our behaviors often stems from our underlying beliefs or philosophies we hold about the world. Therefore, if you can explore a new way of looking at the issue then it is more likely you will find a plausible alternative that can have lasting results. For example, one plausible alternative for avoiding waking up with a hangover is to resolve to never again drink alcohol. While plausible, it doesn’t challenge the underlying belief about why I would drink alcohol to excess in the first place. Not challenging that view my resolution is only avoidance of a headache, not a reframing of my philosophy that drinking is a social custom that must be observed. While I recommend reframing, this can be difficult to accomplish without help from friends, family or a professional like Bob. In lieu of reframing, coming up with two or three good alternatives to your current behaviors is still a good approach that will get you to the next step. Step 3: Present Evidence Just because you have developed some plausible alternatives doesn’t mean you will instantly recognize the alternatives as being better than your current situation. At this stage you only have plausible alternatives that now you need to explore and reinforce with evidence. There is plenty of research that demonstrates we all have cognitive bias, favoring information that helps us maintain our current way of doing things. Therefore, being able to create an actual shift takes a bit of convincing. It is hard to acknowledge that all along the world has been round, not flat. It is hard to acknowledge that a belief you hold might be wrong. To overcome this resistance to change means you need to gather and present evidence. You need to keep in mind cognitive bias and try to find evidence that supports the alternatives. This is not to say blindly accept the evidence, rather to ask the question, “If it is true, how does it change things?” Step 4: Create Relevance When asking how it will change things if true, if there is little or no perceived value then you are not creating relevance. Perceived value over the status quo is important, as without it there is little motivation for enduring change. To help create relevance you need to have a good understanding of your goals, what you are trying to accomplish. Ideally having a vision of what you want to achieve or some future state will help in determining if a particular alternative is relevant. One way to help determine whether relevance has been created is by the degree to which the conflict created in Step 1 has been resolved. Another way is to once again seek out the support of a family member, friend or professional that can help you with discussing the alternatives, the evidence you have gathered and the new path you want to take. The goal is to reduce cognitive dissonance, putting you on track as you head into step 5. Step 5: Provide Scaffolding The final step is to go through the process of testing and reinforcing the relevant alternative. This requires scaffolding, using the evidence you have gathered to prove the alternative is a better or more useful approach than previously held beliefs. It is a process that takes time, learning the potential consequences and implications of a round vs. a flat world. Like a scaffold in construction, the idea is to present lower level concepts first and as those foundations are established you can then build off this foundation, moving to more complex, higher level concepts. An example of scaffolding in education is going from addition to multiplication to calculus. When it comes to sustaining motivational change it requires a similar philosophy, building up the alternative by presenting the evidence you have found over time, not all at once. A Final Note From a general standpoint what is nice about the 5-step model is the ability for anyone to use the model as a stand-alone tool, yet this tool is really only the tip of the motivational iceberg. For a deeper understanding of how the model was developed and how it can be applied, Dr. Hoffman wrote a book titled, “Motivation for Learning and Performance.” In the book there are a number of great case studies along with 50 principles of motivation that can help anyone get a better understanding of what really drives our motivations.  Achieving a goal often requires you repeat certain actions, like going to the gym. A common problem is “The Planning Fallacy,” which is a psychological bias where we tend to overestimate what we can accomplish or underestimate the resources we will require for success. The 2-4 rule is one way to deal with this bias, by establishing an artificial trigger you can use to help monitor and adjust, establishing what frequency and intensity works best for you. The key is finding a good balance. The way the 2-4 rule works is simple. After establishing your actions, if you fail to hit any of your targets two weeks in a row then you might be over extending yourself. This should trigger a reevaluation of your targets, reducing what you believe you can accomplish in a given week. On the other hand, if you hit all of your targets four weeks in a row you may not be challenging yourself enough. This should also trigger a reevaluation, increasing your targets. For example, in an effort to get in better shape you may set a target of going to the gym four times a week for a 30 minute session. If after two weeks you only made it to the gym three times, instead of your targeted eight times, then using the 2-4 rule you would lower your target for the next two weeks. If you have hit all eight sessions, then you may want to consider increasing the frequency, duration, or intensity of your workouts. While I have personally adopted the 2-4 rule as it works for me, there is nothing that stops you from adopting a 3-6 or 2-5 rule. It all depends on the nature of the goal and what works for you. I recommend trying a few different combinations. You can even try different rules for each goal, but I like simplicity so it is rare for me to deviate from using the 2-4 combination. Using the 2-4 rule within a period of a few months you should have a good idea of what you really can accomplish in a given week. Certainly things will change slightly as you improve, the holiday season hits or a life event happens, but using the 2-4 rule gives you a concrete way to deal with our hard-wired tendency to over plan and underperform. Thanks for reading: For a FREE 30-minute course on setting and achieving goals, visit https://www.udemy.com/goal-setting/

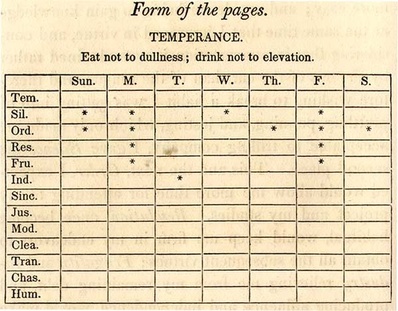

Benjamin Franklin called them virtues; I call them values. In the business world you will commonly see them labeled as guiding principles or core values. By living your values it allows many of your decisions to be made faster, with a higher degree of confidence and with less cognitive effort. The challenge is that all values are not equally embraced. For example, Franklin recognized both industry and chastity as virtues, yet historical records suggest he was much better at embracing the former than the latter. In an effort to deal with the virtues he found most difficult, Franklin developed the following method: Thirteen VirtuesThe first step was Franklin writing down a list of all the virtues he felt would help him better achieve moral perfection. According to Franklin his initial list was of 12 virtues, but then a Quaker friend pointed out that he might want to consider adding ‘humility.' Conveniently this 13th virtue allowed for the second step, where Franklin concentrated on one virtue per week. Given 52 weeks, this meant that four (4) times a year each virtue became the center of attention.

To track his performance Franklin kept a small notebook. Each day he would mark in the book whether or not he felt that he had successfully embraced the virtue. It was Franklin’s version of the quantified self, using pulp or woven-mold paper and a quill pen to create the excel spreadsheet of the 1700’s. Tips for Using the Franklin MethodI’m curious whether or not Franklin really felt the need to work on 13 virtues. I think it possible he just wanted to get to a number that split nicely into the 4 quarters of the year. With this in mind here are a few tips to consider when working on your own virtues, values, or principles.

Using Benjamin Franklin’s Thirteen Virtues as well as the tips provided, I hope this short article has given you a few ideas to help increase your productivity and achieve more success. While Benjamin Franklin was not a saint, it is hard to argue with the influence and accomplishments he achieved throughout his life. Please share this page with friends, family and colleagues. “Better decisions, better lives, better communities.” Academia is crumbling. The venerable business model of Ivy League education is struggling to adjust to the changing face of global education. The same as Steve Jobs revolutionized the music industry with iTunes, where customers no longer needed to purchase an entire album, a similar model is disrupting education. The established model relies on exclusive access to elite professors. In a brick and mortar classroom you can seat a finite number of students. At Harvard the average class size is below 40 with half the courses offered hosting less than 10 students. It was this exclusive access that made the $250,000 price tag for a four-year, packaged degree so valuable.

The new model is destroying this value. Online universities and learning platforms are slowly breaking down the walls, using technology to provide the same information, delivered by the same professors to tens of thousands of students around the globe instead of only a few hundred. The fundamental laws of supply and demand are quickly degrading the value of that $250,000 investment. As the new model takes over, employers are quickly moving from degree based hiring decisions to competency based. Instead of a packaged degree, those looking for a job are more than ever able to compete by demonstrating that they have customized knowledge that is a better fit for the employer. And they are able to acquire this education at a much cheaper price. Imagine in a job interview an applicant that has learned all they know from a single institution in comparison to the applicant that discusses learning psychology from Dan Gilbert and linguistics from Noam Chomsky. Which is more impressive? I realize this future is still a decade or more down the road, yet the $250,000 investment is already rapidly losing value. Online learning is exploding and the gap between those that have access to education and those that do not is quickly shrinking. Globally, from Colombia to India online platforms are being used to build resumes, seek out opportunities and compete. As more people have access, this is drastically impacting supply and demand equations, driving down the cost of education.  There is a direct connection between homicide and learning how to make better decisions. While initially this may seem odd, if you are willing to take a quick journey back in time, I will explain… The English words homicide, genocide, and suicide all trace back to French and then further back to Latin, with the suffix -cide meaning “to kill” or “to cut”. Homicide is to kill a person, genocide to kill a specific group, and suicide to kill oneself. Think of any number of words with the suffix –cide and you will discover plenty of death. The word “decide” is no different. The prefix de- is derived from Latin, meaning “away from” or “off”. Today in Spanish the word “de” means from, of, or off. So decide literally means to “cut off” or “cut away from”. Understanding the etymology of the word “decide” can help transform the way you make decisions.

As you determine which path to try, instead of keeping all of your options on the table, focus on which options you should kill or cut away. Like homicide or any other –cide, when you kill something it is dead, you cannot bring it back to life and this has three significant implications for decision-making:

Better decisions result in more success. Better decisions help with better solutions to problems, improvements in performance, and the ability to achieve the goals you set.

A common goal is to become wealthy, to be a millionaire or to earn $200,000 a year. I want to tell you why you should avoid this trap based on two reasons:

Driven by Performance Money is an outcome measure, not a performance measure. If you love to bake, then some performance measures are the number and quality of the loaves of bread you produce. By focusing on performance you are motivated to tweak your process, improve your ingredients and find ways to supply your delicious bread to hungry consumers. Performance measures are action-oriented. If you charge money for your delicious bread, then one outcome of your performance will be the money you receive. This outcome measure can be helpful, it can be used to benchmark if your bread is more or less delicious than the bakery next door. Regardless, the outcome does not drive performance but rather is a lagging indicator of relative success. I say relative, because it is only a comparison to other bakers. Static vs. Dynamic Measurements When you set a goal to lose 20 lbs. that outcome is static. There will never be a time when a pound of oranges ceases to be a pound of oranges. If you bake bread, a 20 lb. bag of flour will forever remain a fixed measure. On the other hand, money is not fixed but dynamic. If you set a goal to earn $1,000,000 this outcome is constantly fluctuating. Each day the value of currencies rise and fall. Sometimes currencies crash or are devalued. If you are baking bread and the price of grain skyrockets it is a factor out of your control, yet it impacts your goal, right? While an admittedly extreme example, in 1922 a loaf of bread in Germany cost 163 marks. By November of 1923 that same loaf cost 200 billion marks! Just think about anyone living in Germany who set a goal in 1921 to earn 200 million marks within two years. How would it feel to achieve your goal and not be able to afford a loaf of bread? The Bottom Line I recommend you never set money as a goal. Instead, focus on your performance and results will come. Try to use fixed outcomes, not outcomes that will fluctuate. I’m not saying that money as an outcome measure has no value, just be careful not to fall into the money trap.  Courtesy of author Dr. Bobby Hoffman: Motivation for Learning and Performance. Courtesy of author Dr. Bobby Hoffman: Motivation for Learning and Performance.

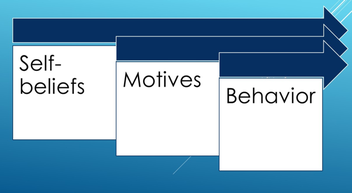

Self-beliefs. Each of us hold a number of different beliefs about the world in which we live. Some are minor beliefs, but others can have a profound influence on success. For instance, to what degree do you believe in destiny, fate, or luck? People that hold a strong belief that control is external will have less personal success than people that believe they are in charge of their own destiny. Beliefs influence our motivation which then shapes our behaviors. One reason behavioral analysis has struggled is the difficulty in tracing an observed behavior to a single root cause. Two people may commit a similar crime (theft), but hold radically different self-beliefs that led to different motivations for the commission of the theft. As the number one enemy of success, there is some good and bad news. The good news is that self-beliefs are adaptive, your beliefs can evolve over time. The bad news is self-beliefs are stubborn and modifying one's beliefs is not a clearly defined linear process. The stubborn nature of our beliefs results in behaviors that are highly adaptive in one environment, but maladaptive in another. Consider a child raised in a large family, developing a strong collectivist belief verses a belief in individualism. As the child leaves the family environment to enter the workforce he or she will most likely find it more difficult to find success in certain industries where a collectivist belief is often maladaptive, e.g. a stock trader or car sales. The bottom line, the beliefs we hold are a powerful key that can drive or inhibit success. The main challenge is that we most often do not even realize how our beliefs and environment interact to influence our motivations and corresponding behaviors. If you want to know how you can combat this enemy there are various techniques that revolve around the larger concept of "self-regulation". It is through self-regulation that both the symptoms and causes of maladaptive behaviors can be addressed. I have included a link to a 1991 article published by Dr. Albert Bandura, arguably the leading expert on self-regulation, and a link to Dr. Hoffman's work which is more current, published in 2015.

Note: This article was initially a response to the question, "What is the Biggest Enemy of Success?" on Quora.com.

Okay, okay, I know my title is a really bad Meghan Trainor reference, but when it comes to making better decisions, using base rates can help you stay out of trouble. From what you pay for insurance to deciding whether or not to start a business, base rates are key to reducing your risks and maximizing results. That said, there is plenty of scientific evidence from psychological studies that demonstrates people tend to ignore base rates. This tendency is a well-established cognitive bias known as "base rate neglect" or the "base rate fallacy". In this article I explain base rate neglect, why base rates are ignored and how you can harness this bias to help you make better decisions.

Explaining base rate neglect. For a real life example, take the $50 opportunity currently offered by insurance giant AIG to provide you “FlightGuard” coverage that guarantees a $500,000 payout to your beneficiary in the event your flight crashes and you die. This means every 10,000 flights without loss of life AIG will make a profit. Now using the base rate we can calculate the extent to which $50 for $500k in coverage is a fair offer. The actual odds that you will die in a plane crash are approximately 1 in 11 million. Based on this base rate, over time AIG is making slightly more than 1,000 times the money they will pay out. Indisputably this is a horrific deal for the consumer. In fact, it is such a bad deal that you would be much better off taking that same $50 and buying fifty lottery tickets in the “Texas Lotto”. The minimum you can win in the lotto is $4 million, 8x the insurance payout. And your odds of winning with 50 tickets are roughly 1 in 500,000 or 22x higher than the odds of dying in a plane crash. Now I’m not saying playing the lottery is a great deal either, but using the base rate I can definitely tell you it is a deal approximately 175x better than buying “FlightGuard” insurance from AIG. Why then do people ignore base rates? This question has been of great interest to psychologists for quite some time and there are a number of theories that revolve around different forms of cognitive bias. Reduced to practical reasons, people ignore base rates due to:

Using base rates to your benefit. Given base rates are often ignored, the same as insurance companies or casinos, you too can profit. You can use base rates to make better decisions, but using a different strategy. Almost every company across a diverse range of industries such as medical, insurance, entertainment and technology use base rates to target millions of consumers who make small, seemingly insignificant decisions. These individual decisions collectively add up to billions in profits, a “nickel and dime” strategy. Your strategy to profit from base rates must be different, basically the opposite of the “nickel and dime” strategy. Instead of targeting relatively insignificant decisions, you will benefit by looking at those major, tough decisions in life where making a mistake may have significant consequences. You need to factor in base rates when making a major purchase like buying a house or car, when deciding to open a business or pursue a specific degree, or more importantly when determining if a risky medical procedure is your best option. Using a risky medical procedure, say heart surgery, let's go through a quick example. Thanks to the Internet there is now a wealth of base rate information only a few clicks away. You can find out what are the base rate odds of surviving the heart procedure, but don’t stop there. You can then begin to adjust from this base by factoring in the base rate performance of specific hospitals and/or specific doctors. In addition, you can find out base rates of post surgery rehabilitation and life expectancies. Using this base rate information can help you make a more informed decision, give you a better chance of surviving the procedure and know what to expect after the procedure is over. In summary, one way to avoid trouble and make better decisions is recognizing that it's all about that base rate. When faced with a tough decision, taking into account the possibility of base rate neglect can improve your chances of success. And if you don’t happen to know Meghan Trainor or the song, then click here to see my shameful attempt at humor.

About the Author:

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist who adamantly denies the existence of a video of him singing "All About That Base".

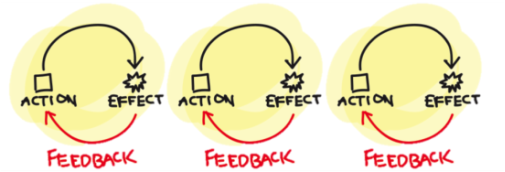

This is the final article in the series on how you can get the most out of using SMART goals. My previous articles discussed establishing goals that are Specific, Measurable, Actionable, and Relevant. Now I want to discuss the final concept, Time Bound. In the article I cover why it is important to include things such as action feedback loops, incentives for process, and the need to account for the psychological principle of the planning fallacy.

Action Feedback Loops A common issue I see when using SMART is failing to harness the time driven power of action feedback loops. If you want to stay motivated and on track, structuring your goals to provide feedback at the correct frequency, i.e. the correct time, is critical to success. Scientific research using both rats and humans has shown that we prefer smaller rewards more frequently than a larger reward that is delayed. Applied to goal setting, this means you want to ensure to establish intermediate time frames to provide the right frequency of feedback and help keep you on the right track in pursuit of a longer-term objective. As an example, take the specific goal to lose 10 pounds in 10 weeks. Do you weigh yourself once and then 10 weeks later weigh yourself again? Or do you weigh yourself twice a day or once a week? Feedback spread too far apart is unlikely to keep you motivated and feedback that is too frequent is not very useful, efficient or actionable. Establishing the correct frequency that works for you is important. You want the frequency to be often enough to give you useful information that is actionable. If you step on the scale once every two weeks, this will provide you actionable feedback about the extent to which your process is working. Speaking of Process and Rewards When you set up feedback based on time, it is not simply to decide “yes” or “no”, did you achieve your milestone or goal. Instead, time is a trigger to evaluate and adjust your process as needed. If after two weeks you have not lost any weight then maybe your process of going to the gym two days a week and eating less than 2,000 calories is not working. This evaluation based on the feedback loop you created allows you to adjust the process and try again. Maybe you need to go to the gym three days a week, try to cut back to 1800 calories a day or maybe you need a new action plan all together. After adjusting your process give it another two weeks and then evaluate again. Over time the adjustments will help you zero in on the process that works for you. Now this may sound a bit odd in a results oriented world, but I personally reward myself for process more so than outcomes. This does not mean I ignore outcomes, but that I choose to focus my recognition on process, because process is what drives results and that is where I want my motivation to originate, from an intrinsic desire to continuously improve my process. If two days a week at the gym and eating under 2,000 calories a day did not result in achieving my milestone of losing two pounds, my first question is did I follow my process? If the answer is yes, then while I may not be excited about the results I do not consider it a failure, rather a lesson in what doesn’t work. If on the other hand I failed to follow the process, then it is another issue all together and a topic for a different article. The Planning Fallacy Another aspect of Time bound, is learning to account for the well-established psychological principle called, the “Planning Fallacy”. Not understanding this principle can help set you up to fail, at least it will feel like failure when after 10 weeks you have not lost all the weight you had expected to lose. On the other hand, if you understand the planning fallacy you can take the results not so much as failure, rather as valuable information that you can use moving forward to make a more accurate estimate in the future. The planning fallacy was initially published by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in nineteen seventy-nine. What they discovered was the tendency for individuals to underestimate the amount of time and resources it will take to achieve their goals. In one study, college students were asked how long it would take them to finish a term paper. The average estimate was thirty-four days. They were also asked to provide an estimate if everything went horribly wrong as well as if everything went smoothly. The smooth scenario, where the grass is green and the skies are blue, resulted in an average of twenty-seven and a half days while the worst-case scenario, where a dog ate your homework; the average estimate was forty-eight and a half days. The interesting thing is that the average actual completion time was fifty-five and a half days, well above even the worst-case scenario. With further studies they found that whether it is an individual prediction or a team effort, the planning fallacy results in project overruns and missed deadlines. A well-known example is the Sydney Opera house, initially scheduled to open in 1963. It took ten years longer than estimated, opening a scaled-down version for roughly 15x the original estimated costs. How could those involved in the project been so bad at planning? Why You Can’t Plan There are a number of theories as to the psychological reasons we are so bad at estimating into the future. One of the more popular theories is that when we recall our past performance, any delays we experienced, we tend to attribute those delays to external factors that were beyond our control, while discounting any factors related to our personal performance. Another theory is that when making future predictions, it is difficult to estimate the cumulative factor of small, individual distractions and mishaps that will occur, such as an unexpected phone call. Instead, we only look at the major elements we believe we can control and build future predictions based on this ideal scenario. So what can you do to deal with the planning fallacy? The number one way technique is to make sure that you anchor any future predictions based on your actual past performance. This means to avoid substantially altering predictions without having a very good reason to expect different results. It does not mean to ignore projected changes or benefits of a new idea, method or process, but just to make sure that any predictions of improvement or growth are firmly rooted on the foundation of your past results. The Bottom Line When it comes to establishing SMART goals, you want to harness the power of time by making sure that your goals are Time Bound. This means making sure that you consider things such as;

To put it all together, the SMART format is a structured method to goal setting that provides an evidence-based approach to achieving your goals. While it is not the panacea for all of the challenges we face in life, if you have read all of the articles, it is another tool that you can now place on your metaphorical tool belt. You now have the means to use SMART as a way to establish and monitor goals that are specific, measurable, actionable, relevant and time bound. If you have not read the other articles, you can use the following links: Specific Measurable Actionable Relevant If you have any questions or suggestions, please contact me at richard@decisionskills.com.

About the Author:

Richard Feenstra is one of the unfortunate individuals in life, cursed with getting just slightly better looking each day. By the time he is in his 90's he will be an international heart throb. During the meantime, Richard enjoys sharing what he has learned over the years about the art and science of decision-making. (Keywords: cognitive dissonance, Maslow's hierarchy of needs, goal setting, scaffolding, cognitive bias, judgment, bounded rationality, SMART goals, motivation, self-regulation, goal achievement.) |

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed