Designing Ethics: Would You Throw the Fat Man Off the Bridge?

|

The toughest decisions you face in life are often ethical dilemmas. I think understanding the psychology of ethics can help shed some light on those decisions, so today that is what I want to discuss. As you read, ask yourself, “How would I respond?”

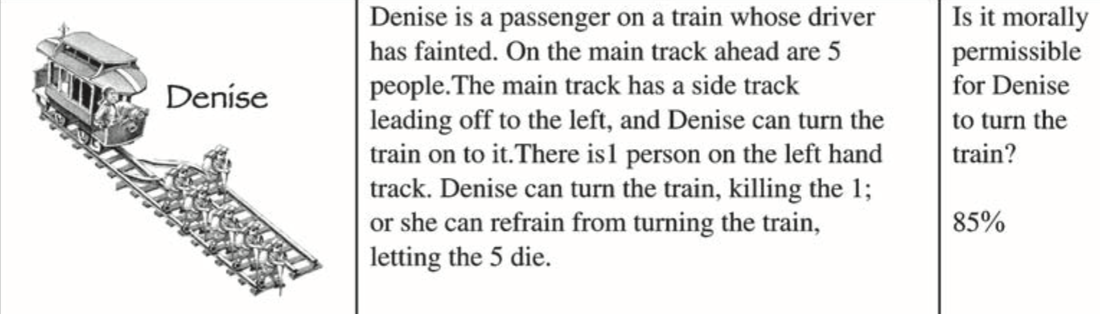

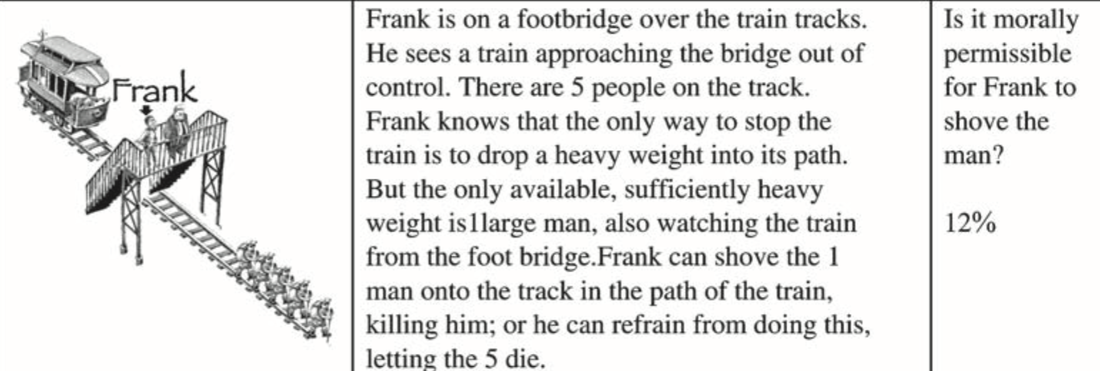

The original trolley experiment was conducted in 1967. The basic concept is a runaway trolley is headed towards five people stuck on the tracks. On another track is only one person. In one version you must decide whether or not pull a lever that switches the path of the trolley, resulting in one death instead of five. Would you pull the lever? A 2011 experiment conducted by Carlos David Navarrete out of Michigan State University, found that 90.5% of people would pull the switch. Out of 147 participants, 133 pulled the switch, while 14 did not. Also interesting is that 3 pulled the switch, but then decided to return the switch to its original position. From a purely utilitarian perspective, five lives are more important than one so why would anyone not pull the lever? The reasonable conclusion is that ethical decisions are made on merits not effectively explained by utilitarian principles. People struggle with playing an active role and in some cases do not want to interfere with fate or destiny. The thought process of those 14 people that leave the lever in the original position feel by not being involved they are not responsible for the deaths of anyone, but by switching the lever they are directly responsible for the death of at least one person. And now a twist. A variation of the original trolley experiment is called the, “Fat Man Problem.” Instead of two tracks and a lever you can pull, there is a single track that runs beneath a bridge. There are five people stuck on the track and on top of the bridge stands a man much heavier than you, heavy enough to derail the trolley. You are behind the man. Only by pushing the fat man off the bridge can you save the five, but it means the fat man will die. Would you push the man off the bridge? In an experiment in 2007 by Marc Hauser and colleagues, they posed the “Fat Man Problem” and the original track-switching scenario to 5,000 participants. Consistent with Navarrete’s findings, the results showed 85% of people will switch the track, yet when faced with the fat man scenario, only 12% of people will push the man off the bridge. Why such a huge difference? In both scenarios the outcome is the same, either one person or five people die. Researchers conclude that this difference reinforces that psychology rather than utility is at the heart of ethical decisions. It is our underlying beliefs and values that define how a problem is framed and this can make a major impact on what you decide.

The Big Picture: Ethical Design While the trolley problem is just a thought experiment, the big picture takeaway is the ability to contrast approaching a problem from a utilitarian perspective with an ethical perspective. Using ethical design means the possibility that some efficiency might be lost in an effort to preserve a moral principle. If for instance a community decides that saving five lives is indeed the preferred outcome over one life, we can design systems, metaphorical switches, that help guide decision-making. A real world example of psychology used in ethics design is the system for consenting to be an organ donor and the use of opt-in or opt-out forms. Germany has an opt-in system, resulting in 12% of the population making the decision to donate. Austria, a country with very similar demographics, uses an opt-out system. When registering for a license, people must check that they do not want to be an organ donor. This subtle difference has almost 99% of Austrians as registered organ donors. More Information Ultimately even the ethics behind ethics design runs the risk of being considered unethical, but the ethics behind the decision to use psychology to manipulate behavior is left for another discussion. For now, if you would like to learn a little more about the trolley problem, check out the videos. |

References

Bonnefon, J. F., Shariff, A., & Rahwan, I. (2016). The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles. Science.

Hauser, M., Cushman, F., Young, L., Kang Xing Jin, R., & Mikhail, J. (2007). A dissociation between moral judgments and justifications. Mind & language, 22(1), 1-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0017.2006.00297.x retrieved: http://cushmanlab.fas.harvard.edu/docs/hauser&etal_2007.pdf

Workman, L., & Reader, W. (2014). Evolutionary Psychology: An Introduction (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organ_donation#Opt-in_versus_opt-out

http://healthland.time.com/2011/12/05/would-you-kill-one-person-to-save-five-new-research-on-a-classic-debate/

Bonnefon, J. F., Shariff, A., & Rahwan, I. (2016). The social dilemma of autonomous vehicles. Science.

Hauser, M., Cushman, F., Young, L., Kang Xing Jin, R., & Mikhail, J. (2007). A dissociation between moral judgments and justifications. Mind & language, 22(1), 1-21. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0017.2006.00297.x retrieved: http://cushmanlab.fas.harvard.edu/docs/hauser&etal_2007.pdf

Workman, L., & Reader, W. (2014). Evolutionary Psychology: An Introduction (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Organ_donation#Opt-in_versus_opt-out

http://healthland.time.com/2011/12/05/would-you-kill-one-person-to-save-five-new-research-on-a-classic-debate/