Social Reciprocity: The Science of Giving

Hard wired into our mental DNA is the need to reciprocate.

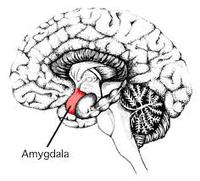

When we receive a gift, the regions of the brain associated with emotion and decision-making light up. Studies on the social and psychological aspects of this activity show that receiving a gift triggers a cognitive dilemma that must be resolved. The easiest way to resolve the conflict is to give something in return of equal or greater value. In psychology this is known as the theory of reciprocity or social reciprocity.

The Science

The "Coca-cola" experiment is probably the most well known study on reciprocity. It was published in 1971 by Dennis Regan. In the study, participants believed they were there to evaluate paintings. Also in the room was a fellow participant named Joe, but Joe was really Regan's assistant.

First, Regan manipulated the degree to which a participant liked Joe, by having the subject overhear Joe being either polite or rude to a person during a phone conversation. In one condition, Joe would leave and bring back two soft drinks, giving one as a gift to the participant. In another condition, Joe would leave and return empty handed. After evaluating some art, Joe was then left alone with the participant at which point he would hand them a note, asking them to buy some raffle tickets.

The results of the study showed the power of giving. In the condition where Joe did not give the participant a soda, the degree to which they liked Joe influenced how many raffle tickets they would buy. But, in the condition where Joe did give a soda, participants bought twice as many tickets as the no soda condition, regardless of the degree to which they liked Joe. So not only did people that did not like Joe buy tickets at twice the rate, they buy many more raffle tickets than the cost of the soda.

When we receive a gift, the regions of the brain associated with emotion and decision-making light up. Studies on the social and psychological aspects of this activity show that receiving a gift triggers a cognitive dilemma that must be resolved. The easiest way to resolve the conflict is to give something in return of equal or greater value. In psychology this is known as the theory of reciprocity or social reciprocity.

The Science

The "Coca-cola" experiment is probably the most well known study on reciprocity. It was published in 1971 by Dennis Regan. In the study, participants believed they were there to evaluate paintings. Also in the room was a fellow participant named Joe, but Joe was really Regan's assistant.

First, Regan manipulated the degree to which a participant liked Joe, by having the subject overhear Joe being either polite or rude to a person during a phone conversation. In one condition, Joe would leave and bring back two soft drinks, giving one as a gift to the participant. In another condition, Joe would leave and return empty handed. After evaluating some art, Joe was then left alone with the participant at which point he would hand them a note, asking them to buy some raffle tickets.

The results of the study showed the power of giving. In the condition where Joe did not give the participant a soda, the degree to which they liked Joe influenced how many raffle tickets they would buy. But, in the condition where Joe did give a soda, participants bought twice as many tickets as the no soda condition, regardless of the degree to which they liked Joe. So not only did people that did not like Joe buy tickets at twice the rate, they buy many more raffle tickets than the cost of the soda.

Application

Since the "Coca-cola" study there have been numerous experiments that confirm that when you give, you shall receive. This is great if you are giving in a principled manner, but this is where the slippery slope of ethics enters the equation.

Marketers use the principle to generate revenue. When you receive a letter in the mail asking for donations, it often comes with something for free. Years ago it was a small packet of stamps or address labels. Recently, I received a letter from a non-profit organization that contained a brand new, crisp, one dollar bill.

At a shopping mall if you go near the food court there is almost always someone handing out free bites of their most popular items. Go to a trade show and you will walk away with a bag full of "freebies" or "swag". Surf the Internet and inevitably you will be offered a free newsletter, samples, or a free trial.

It is up to you to decide where to draw the ethical line, how exactly you want to use this tool in influencing others to help achieve your goals. Personally, don't send me a crisp dollar bill, I know you don't really care about me and I see it as intentional manipulation. On the other hand, keep the free samples coming in the food court. I think you believe in your product and just want to offer me a tasty treat that might just convince me to take a seat.

Since the "Coca-cola" study there have been numerous experiments that confirm that when you give, you shall receive. This is great if you are giving in a principled manner, but this is where the slippery slope of ethics enters the equation.

Marketers use the principle to generate revenue. When you receive a letter in the mail asking for donations, it often comes with something for free. Years ago it was a small packet of stamps or address labels. Recently, I received a letter from a non-profit organization that contained a brand new, crisp, one dollar bill.

At a shopping mall if you go near the food court there is almost always someone handing out free bites of their most popular items. Go to a trade show and you will walk away with a bag full of "freebies" or "swag". Surf the Internet and inevitably you will be offered a free newsletter, samples, or a free trial.

It is up to you to decide where to draw the ethical line, how exactly you want to use this tool in influencing others to help achieve your goals. Personally, don't send me a crisp dollar bill, I know you don't really care about me and I see it as intentional manipulation. On the other hand, keep the free samples coming in the food court. I think you believe in your product and just want to offer me a tasty treat that might just convince me to take a seat.

References

Kawai, N., Yasue, M., Banno, T., & Ichinohe, N. (2014). Marmoset monkeys evaluate third-party reciprocity. Biology letters, 10(5), 20140058.

Regan, D. T. (1971). Effects of a favor and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7(6), 627-639.

Sakaiya, S., Shiraito, Y., Kato, J., Ide, H., Okada, K., Takano, K., & Kansaku, K. (2013). Neural correlate of human reciprocity in social interactions. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7, 239. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00239

Regan, D. T. (1971). Effects of a favor and liking on compliance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 7(6), 627-639.

Sakaiya, S., Shiraito, Y., Kato, J., Ide, H., Okada, K., Takano, K., & Kansaku, K. (2013). Neural correlate of human reciprocity in social interactions. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 7, 239. http://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2013.00239

Available Resources

| regan_1971_reciprocity.pdf |