|

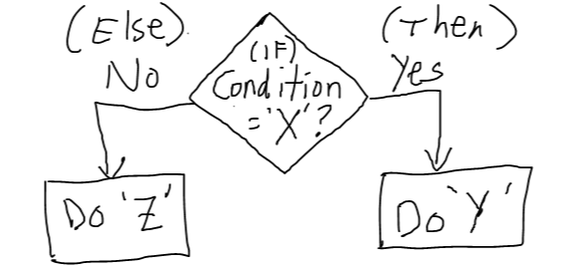

When struggling to achieve a particular goal, consider incorporating the use of pre-decisions to increase your chances of success. In over 94 studies the use of pre-decisions has shown to help get you started, keep you focused, conserve cognitive resources, and if for some reason you do become distracted, pre-decisions can help get you back on the right track.

0 Comments

The power of memory is elusive. It is difficult to quantify, yet it is undeniable that memories are often times what we yearn to create. The goals you set are also almost always tied to creating memories, or at least they should be, as the power of memory can help you maintain your motivation.

Salient vs. Gist Memory Consider the difference of setting a goal to run the Boston Marathon verses the more general goal to lose ten pounds.

By Dr. Bobby Hoffman

Companies often devote massive resources toward employee education under the assumption that enhancing employee skill sets is beneficial for both the individual and the organization. The corporate investment in employee development is based on the company’s expectation of enhanced skill sets, increased productivity, and a positive relationship between training hours and profitability. However, training employees comes with a price. One intangible cost is worker negativity and lack of enthusiasm toward training participation. Post-training repercussions include complaints about time away from work and the perception that little personal gain resulted from the developmental experience. Here are four research-supported strategies that enhance training motivation: With driverless cars on the horizon there is renewed interest in a classic ethical dilemma, the trolley problem. What decision would you make?

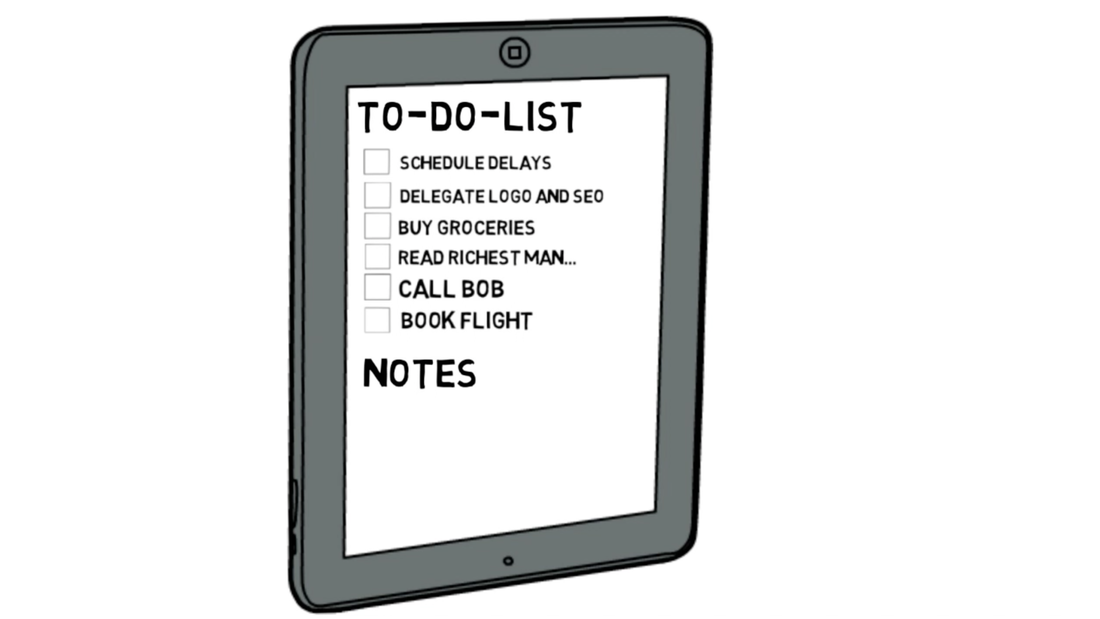

You spot a trolley barreling down the track towards five workers. There is a lever you can pull to switch the trolley over to another track, but there is a worker on this track as well. You quickly assess and other than the lever, there are no other feasible options. It is either one life or five lives. Do you pull the lever? If you’re like me, it’s fairly common for certain items on your to-do-list to linger, taking much longer to accomplish than you had originally planned. In some cases the item never gets done and mysteriously fades away, not making it onto the “revised” list. Why? It is not as if creating to-do-lists is a novel concept.

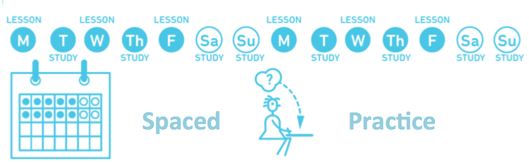

The Planning Fallacy One explanation is based on psychological research conducted by Daniel Kahneman and Amost Tversky. Back in 1979, they discovered that research subjects had a tendency to underestimate the amount of time required to accomplish a task. This cognitive bias is most often referred to as, “The Planning Fallacy.” Since 1979 hundreds of studies have replicated their findings. One such study took place at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, Canada. College students were asked by researchers to predict how long it would take to write their thesis. The average estimate was just over 34 days. The students were also asked to guess how long it might take if everything went smooth, as well as to estimate how any potential delays might impact their original estimate. Respectively, the average estimates were roughly 27, and 48 days. In reality, the average time it took for students to turn in their thesis was 55 days, a full week past even the worst-case estimate and over 50% longer than the base estimate. And time is not the only thing we underestimate, we also tend to underestimate resources that might be required. In a 2002 study, homeowners that were planning to remodel their kitchens were asked to estimate how much it would cost. The average estimate was $19,000, while the average cost was actually $39,000, over double the original prediction. The planning fallacy is not limited to individual judgments, but groups and organizations as well. Have you ever heard stories of government projects where a hammer ends up costing over $400, or a $600 dollar toilet seat? While these types of inflated prices are not entirely products of the planning fallacy, it is undoubtedly a factor. What about the case of the Sydney Opera house? In that case, a $7 million dollar project ended up costing $102 million and took 10 years longer to complete than originally projected. For some actual research data, there was a 2005 study of railway projects that showed that over a period of 30 years, four out of every five projects significantly over estimated how many passengers would end up using the system. Explaining Bias There are a number of theories that try to explain why we are so bad at estimating into the future. One theory is that it is a self-serving bias to be a bit overly optimistic, that while our beliefs might be less than accurate, it helps provide the initial momentum required to take on a challenge. In doing so, our memory of past events is less than accurate. When we recall past performance, any delays we tend to attribute to external factors that we safely label as, “Not my fault.” These are factors that we rationalize were beyond our control and therefore should not influence future predictions. At the same time, we tend to discount any factors related to our personal performance and rationalize an increase in our abilities to stay motivated or a renewed commitment to the goal. Another theory is not as positively framed, but offers to explain our tendency to be poor planners based on known limitations of our cognitive abilities. The theory suggests that in making future predictions, individuals construct a mental narrative or general story that has them accomplishing the task. This story will only include the major elements that are known variables. Small, individual distractions and mishaps that will occur, such as an unexpected phone call are not factored into the equation. Given these small distractions are by and large unknowns, any estimates will understandably be incorrect. It is not bias, rather an inability to account for all the variables. Fallacy Fixes There are a number of ways to try and deal with the planning fallacy. Two of the methods are based on scientific research and the last fix is common practice in the field of project management. -1- Anchor and Adjust: According to some research, the best way is to anchor your future predictions based on objective past performance. If the last time you went on a diet you lost an average of 1 lb. a week, that’s what you should use to estimate the next time you want to lose some weight. This does not mean to ignore projected changes or benefits of a new idea, method or process, but to use past performance to anchor and then adjust. -2- List Delays: Another evidence-backed technique is to intentionally consider setbacks. A study in two thousand and four showed that estimates were more accurate after participants considered three obstacles that might impede their progress. To use this technique, simply do the same…anytime you set a goal or are trying to estimate the time or resources required to finish a task, include a step where you create a list of any potential delays. -3- Add-X: Similar to listing delays, this method can help by starting with the base assumption that any projected timeline is by default underestimated. The question then is how much time do you add? For a defined task that is simple with no hidden variables add 10% to the original estimate. For an ill-defined task that is complex with unknown variables add 50% to the original estimate. If it is a novel task never before attempted, add 100%. The Add-X method is understandably a judgment call, as what is a simple task for one person is a complex task for another. If I try to repair my own car I don’t have the knowledge or skills. It is a complex task with plenty of unknowns for me. If a repair manual I find online says it should take an hour to fix, I should probably go ahead and plan for it to take double the amount of time. On the other hand, for a professional mechanic it is a simple task without unknowns. Still, the mechanic should add at least 10% to account for any unexpected distractions or mishaps. Summary The next time you are creating or updating your to-do-list, think about the planning fallacy. Think about the science behind our natural tendency to over estimate what we can accomplish and underestimate the time and resources it will take to accomplish the goals we set. While ultimately there is no known method that actually eliminates cognitive bias all together, there are techniques that you can use to try and offset the planning fallacy. Whether you or someone you know is headed back to school or you have set a goal that involves learning, like speaking a foreign language, there is a wide range of strategies you can use that will help you to learn more efficiently, maximizing your time and effort. In this article I want to share with you 7 of these strategies, backed up by scientific evidence. Strategy One: Spaced (Distributed) Practice You can boost your ability to retain information by scheduling several small study sessions, spacing them out over time. This has proven more effective than the age-old practice of “cramming.” To get the most out of spaced practice, make study sessions shorter and give yourself plenty of time between sessions. Instead of a single five (5) hour marathon session, break it down into one (1) hour sessions that take place over several days or a week. If you are studying multiple subjects, break it up so that you are rotating between subjects. The reason spaced practice is so effective is that it helps you to focus on the more important concepts, prompts the need to recall from previous sessions, and limits the time available to become distracted by irrelevant material. The most challenging aspect of spaced practice is having the discipline to create a schedule and then following through. If you find it difficult to stick to your schedule, consider adjusting the frequency or take a look at your overall workload.  Strategy Two: Concrete Examples Learning has proven more effective when a person learns in context, being able to visualize how they can apply what they are studying in the real world. This can be more or less difficult dependent on the extent to which a person can attach what they are learning to a concrete example. There are primarily three ways to take learning from the abstract to the applied:

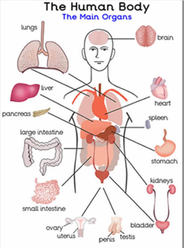

Regardless of how you connect what you are learning to a real world application, the thing to remember is to try and attach it to a concrete example. Getting people involved by providing a concrete example helps both in understanding and retrieval of the material. “Tell me and I forget. Teach me and I remember. Involve me and I learn.” – Benjamin Franklin  Strategy Three: Dual Coding Have you ever heard that pictures are worth 1,000 words? With the explosion of the Internet more and more research is proving that combining words with visuals helps people better retain information. The process of using text with visuals is called dual coding and it can come in a variety of forms:

For example, if you are trying to learn anatomy, such as the kidneys, liver, lungs, heart, and brain, then having a diagram of the human body can help over using flash cards that only contain text. According to research, pictures are processed 60,000 times faster than text and visuals are processed using an area in the brain associated with long-term memory, while text uses working or short-term memory. When using dual coding, start by initially connecting text with a visual reference and work your way up to more advanced techniques, drawing the visual from memory. This is can be especially useful in multi-media learning. Strategy Four: Elaboration This strategy asks how or why something works in a certain way. From the original question you begin to dig deeper, searching for additional resources and materials that can help provide answers. The process of elaborating helps you build a better understanding. When using elaboration it can help to compare and contrast opposing ideas. You may want to seek out opinions and have discussions with friends or colleagues. In a technology rich environment you can use the Internet to access previous research on the subject. When using elaboration, there are at least two things to keep in mind:

Strategy Five: Interleaving This strategy works great in conjunction with spaced practice. Interleaving is the intentional switching and rearranging of topics during a study session. Study one topic or subject for a short period of time and then switch. Interleaving is best used when topics have some crossover or similarities. For instance, when studying to learn a foreign language you may (a) read a short story, (b) memorize new vocabulary, (c) practice conjugating verbs, (d) have a practice conversation, etc. In a study session you may want to split up a long session into a,b,c, then d,c,a, then b,d,a. By mixing up the topics and switching periodically it will help you to make connections between the material and gain a better overall understanding. Be careful not switch between topics too often. A good rule of thumb is to spend at least 45 minutes, but it really depends on what you are trying to learn. Interleaving can also be used with subjects that have limited crossover, such as studying biology and then economics. While making connections between diverse subjects is not likely, switching gears can help promote critical thinking skills. Strategy Six: Retrieval Practice This is a great strategy to begin a study session, by first reviewing any previous material. In Robert Gagne’s, 9 events of instruction, stimulating the recall of prior material is an important aspect of helping to learn new material. The best way to use retrieval practice is to leave all of your books and materials from a previous study session closed. Take out a pen and paper and either create a list or draw as much as you can remember. For instance if you are studying anatomy you might be able to draw a body and place organs in roughly the correct locations, even if the names of the organs escape your memory. Another way to practice retrieval is by using flashcards or quizzes. Dependent on what you are trying to learn the material may already come with some pre-made tests. If you are studying with a friend, you can take a few minutes to quiz each other on the main concepts or ideas. Strategy Seven: Gamification The last strategy you can use to help improve your learning is called gamification. This is where you take the material you want to learn and use different techniques to turn the lessons into a form of game. This can be combined with other learning strategies to help boost motivation. For instance, if you have decided to use retrieval practice, instead of a simple quiz, you might decide to create a home version of the popular television game show, “Jeopardy”. More advanced forms of gamification use the learning objectives and materials to provide various incentives, such as leveling up, badges, unlocking rewards or in some cases imposing some form of penalty. Gamification taps into the affective components of learning. A person can become more motivated to learn if they feel a sense of accomplishment as they level up. Conversely, some types of gamification harnesses loss aversion, the psychological fear of losing a reward previously gained. There is a balance when using this strategy to make sure you are not too distracted by the game, in lieu of actually learning the content. I remember playing Oregon Trail, a game designed to teach about settlers crossing the American West. One aspect of the game allowed for hunting, which became a distraction over learning concepts more central to that time in U.S. history. Summary

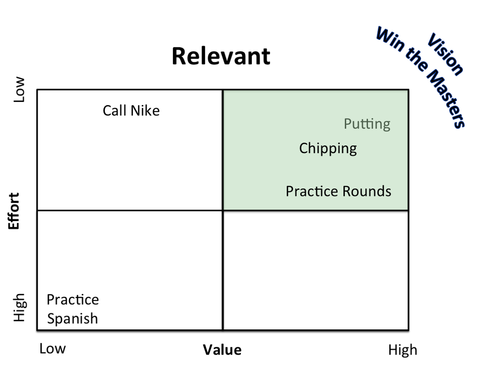

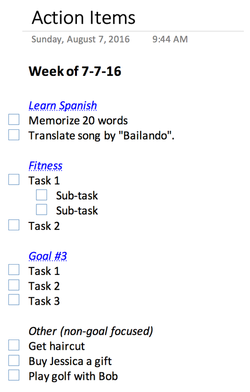

Whenever you set a goal that involves learning, consider using strategies that can help you maximize your effort. There is no reason for you to pursue any serious goal without taking some time to develop a solid plan to help you achieve your goal in less time or using fewer resources. I want to take a moment to credit learningscientists.org for this article. Six of the seven strategies discussed in this article have free posters that you can download here, for free. References Benjamin, A. S., & Tullis, J. (2010). What makes distributed practice effective? Cognitive Psychology, 61, 228-247. Mayer, R. E., & Anderson, R. B. (1992). The instructive animation: Helping students build connections between words and pictures in multimedia learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 4, 444-452. McDaniel, M. A., & Donnelly, C. M. (1996). Learning with analogy and elaborative interrogation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 88, 508-519. Rawson, K. A., Thomas, R. C., & Jacoby, L. L. (2014). The power of examples: Illustrative examples enhance conceptual learning of declarative concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 27, 483-504. Roediger, H. L., Putnam, A. L., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten benefits of testing and their applications to educational practice. In J. Mestre & B. Ross (Eds.), Psychology of learning and motivation: Cognition in education, (pp. 1-36). Oxford: Elsevier. Rohrer, D. (2012). Interleaving helps students distinguish among similar concepts. Educational Psychology Review, 24, 355-367. Wong, B. Y. L. (1985). Self-questioning instructional research: A review. Review of Educational Research, 55, 227-268. It has been a bit longer than usual for me to post an article. My time in Ecuador came to an end and now I am back in the United States helping with a family move. Next, I am headed to China. In this article I want to address a series of three (3) insightful questions posed by a student, Jessica Kayembe, in my course on using SMART Goals to achieve more success. -1- How do you align your goals to your vision? Sometimes I usually go ahead and write a bunch of goals to achieve, however you mentioned that our goals should be aligned with our vision, hence my question. On this note, does it mean that before any goal setting, a vision must be in place? I hate to say a vision “must” be in place, but I do think without a vision it is almost impossible to take action. Generally speaking, goals are middlemen between a vision and actions, i.e. vision -> goals -> actions. The sport of golf can be used as a good analogy. My big vision is standing on the 18th green at the Masters having just sunk my last shot. The crowd goes wild. Not only did I win the tournament, I just broke the course record! The above paragraph is a vision, a mental picture of some end state or outcome that I want to achieve. It doesn’t matter necessarily how far fetched the vision, rather the extent to which I can see clearly what it is I a want to obtain. To make my vision a reality, I could just take action. Remember, goals are the middlemen. I don’t really need to set any formal goals. I could just grab my clubs and head to the first tee box. But, does that give me the best chance of success? If I want to improve my chances, I set goals. I look at the course and develop a strategy for each hole. I create an action plan, not only for the course, but to help me prepare leading up to the tournament. Based on the action plan I can establish a specific, but challenging goal to score five (5) under par. If the course has a lot of sand traps, I set additional goals, for instance, a goal that focuses on striking golf balls from hazards. Now imagine it is the first day of the tournament and a thick fog rolls over the course. Imagine you have not set any goals. You are standing on a tee box, but can’t see more than ten feet. You lack vision. While you may know that your immediate goal is to drive your ball toward the flag and get the ball in the cup in as few strokes as possible, it will be much more difficult than on a clear day. Without vision, you can still set a goal, you can still take action, but imagine how much more difficult it will be to achieve. Clarity of vision helps. Aligning my goals to my vision. Remember that in the SMART format, I use ‘R’ as relevant. You can think of relevant as the component of SMART that checks to ensure your goals are in alignment. In my big vision there is a roaring crowd as I sink my final shot to win the Masters. I have three-months to get ready. I set my goal to shoot 5 under par each round of the tournament. My goal is specific and time bound. In support of this larger goal, I create sub-goals or milestones. With each goal or action I can ask myself if it will help me, if it will support me, and if it is relevant to turning my vision into reality. If the answer is yes, then it is aligned, it is relevant to my vision. If the answer is no, then it is not in alignment. For example, which of these goals and/or actions are aligned and which are not? Within one week (time bound); -a- Land 300 balls within 5 feet of the flag from 150 yards. -b- Memorize 20 new words in Spanish. -c- Sink 500 putts from 10 feet. -d- Play 2 practice rounds. -e- Call Nike to see if they will sponsor me in the tournament. Clearly, memorizing 20 new words in Spanish is not relevant to achieving my vision of winning the Masters. If I have another vision I am working toward, it still might make it on my to-do-list for the week, but it is not relevant or aligned with my vision to win the Masters. Call Nike? I think the degree to which that action is relevant or aligned with my vision of winning the Masters can be debated, but I would argue it would be much less relevant than the other goals/actions related to actually practicing golf. This is why in the course in the lecture on ‘Relevant’ I discuss the value/effort matrix. While asking the question on whether an individual action or goal is or is not relevant can be useful, when you have a number of goals it can also help if you try to prioritize which ones are most relevant. When using the matrix, remember that any goal that challenges you will hopefully require a decent degree of effort. Therefore, it is a process of evaluating the relative effort between available goals or actions and the corresponding value in moving you closer to your vision. It is not about evaluation of any one goal or action, independent of the others. I hope the above answers, (1) if you must have a vision before setting a goal and, (2) how you help to ensure your goals are aligned with your vision. 2. Sometimes I just brainstormed a bunch of to-do list based on what I want to achieve during the day, I would like to know the difference between a to-do list and a goal and how can I have my mind set onto differentiating them. Because I am sure there is a difference between them. Yes, there is a difference between a formal, structured goal and a to-do-list. It can be confusing at times. A structured goal is a specific outcome that can be measured and is time bound, such as to score 5 below par within 3 months. This is not the same as a generic task to play a round of golf with Bob. A task is written down without taking the time to consider the degree to which it is specific, measurable, relevant, or time bound. While by chance a task might meet some of the criteria of the SMART format, this happenstance does not then make it a formal goal. Playing golf with Bob is just on your to-do-list and is not a formal goal you are trying to achieve. How I organize my to-do-list. While it is semantics, I call my to-do-list my “Action Items”. This makes it clear to me that the list is focused on my actions, specifically the very next actions I need to take. What next actions do I typically have on my list? Those actions that are either aligned with my goals, or actions related to routine logistics or other commitments, e.g. “Get a haircut”, or “Buy Jessica a gift”. Periodically I review my action items using the 80/20 rule. Ideally, I want no more than 20% of my items to be routine logistics or other commitments and 80% to align with my goals. If I find my list way out of balance, it lets me know I am losing focus, that I am allowing myself to become distracted and making too many commitments that are not goal oriented. As for brainstorming my to-do-list, I have a routine that I have been following for several years that I call, “Planning Sunday”. Having used this routine for so long, it now only takes around 30 minutes, no longer than an hour. Planning Sunday involves reviewing my action items from the previous week and updating my progress on my goals, enjoying any successes and celebrating my failures. As part of this process, I establish my action items for the upcoming week. After I have my action items listed for my formal goals, then I conduct a mini brain dump. I think of any items I may have forgotten, I list items related to routine logistics and then I write down any thoughts until my mind is clear. The brain dump includes writing down any notes or ideas that I don’t want to forget, regardless of how relevant. My final step is to go back over my action items for the week and ask myself if I have fallen victim to the planning fallacy. Basically, I ask myself if I can accomplish the action items I have listed? When I feel positive about my list, I’m ready to take on the week. When Monday comes, I focus on the list and checking off each action item. During the week I am typically not focused on my vision or goals, rather I am primarily focused on execution of individual items. For me personally, I do not believe brainstorming each day to determine what I want to achieve that day would work for me. It is too short a cycle. For some, daily planning may serve them well, while others may find reorganizing their mind once a month more helpful. For me, once a week using planning Sundays seems to work out best. The end product is a to-do-list that looks something like the above. I use Microsoft OneNote, but there are plenty of comparable programs. I also include a place for me to take notes throughout the week.

Note that “Learn Spanish” or “Fitness” are just headings that serve as reminders of the current goal. To go to my goals written using SMART, OneNote allows me to insert links to other pages. Clicking on “Learn Spanish” takes me to a full description of the goal where I can log my progress or make adjustments. 3. Now based on the course, one has to be specific when setting goals, yet a vision must be the driving force behind the setting of goals. Could you please elaborate on that and if that sentence of mine is correct based on the course you gave. Hopefully the response to the first question also helps to answer this final question. I don’t want to say a vision “must” be the driving force, but it certainly does help. The more clear and precise a vision, the easier I think you will find it to establish specific goals. It is much more difficult to fly blind. Remember, a goal is a middleman between vision and actions. The course is about using SMART as a model to help provide structure, to help bridge the gap between what you can envision and the actions you will need to take to get there. It is not that you can’t envision yourself standing at the top of a mountain and then just start hiking, but if you want to give yourself a higher chance of success, a higher chance of actually reaching the top, then it is a good idea to establish some goals in support of your vision. Remember: Vision -> goals -> actions Let me know your thoughts. How do you organize your to-do-list?

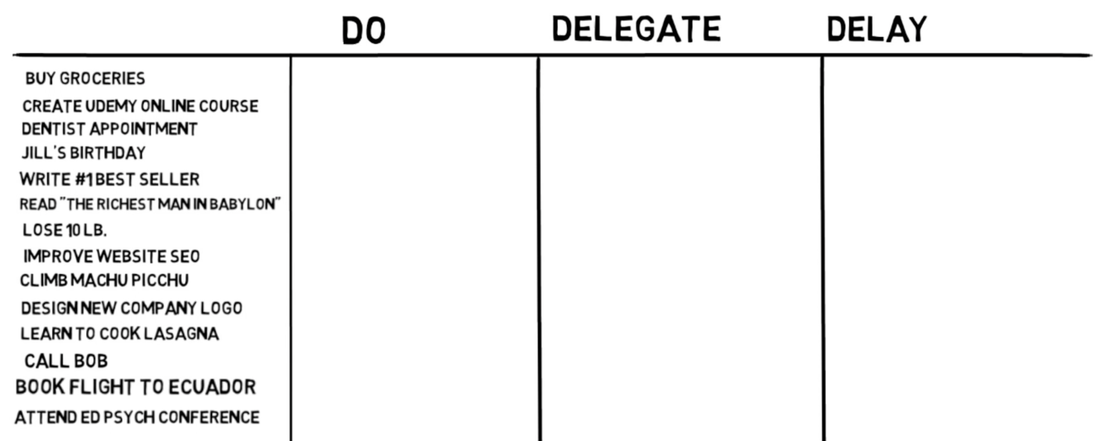

To organize a to-do-list, one tool that you can use is the 4 D's. For every item on the list, you are either going to do it, delegate it, delay it, or dump it. While this might seem rather straight forward, there are few tricks to getting the most out of the method.

Create a Comprehensive List The first thing you want to do before organizing your to-do-list is to make sure you have a complete list. The list should include individual tasks, but can also include any projects or ideas you have floating around in your head. This process of creating an exhaustive list helps clear your mind, reducing cognitive fatigue. In fact, researchers E.J. Masicampo and Roy Baumeister discovered that similar to the Zeigarnik Effect, organizing your list actually helps free up cognitive resources, allowing you to be more productive and focused. After you have a comprehensive list, it is time to clean it up. To do this, create three columns with the labels "Do", "Delegate", and "Delay".

Delegate or Outsource

Now you want to go through and decide on any items you can delegate. This includes items you can outsource. In the digital world this includes cost effective solutions like upwork.com, fiverr.com and Amazon's mechanical turk. Do Once you have figured out the items you want to delegate, go back over the list and pick the items you believe are your high priority items that you want to accomplish within the next seven (7) days. If this is your first time using the process you will want to pick a start or end of your week, such as using Sunday or Monday. Delay Next you want to look for any items you can schedule to do later. Put those under the delay column. This may include recurring items, such as birthdays or filing taxes. It can also include items you wrote down that need to be structured, that need to be planned and broken down into smaller tasks. For example, you may want to publish a book or take a vacation. These are not tasks you normally accomplish in 7 days, requiring you schedule a time when you will assess the item and determine next steps. Dump or Archive At this point, the only items remaining on your list are those that did not fit under the first three columns. These are items that you need to dump. Before the digital age, to dump it meant to literally toss those items into the waste basket or if you felt you might want to save them for later you placed them in a manila folder in a metal filing cabinet. Today you can think of dumping it more as a digital dump with the option to either delete the item or you can archive your ideas electronically. Personally, I have an archive folder that is searchable. This allows you to retain your ideas or notes in a safe location while keeping your mind decluttered, allowing you to focus on your high priority items. Finalizing Your List With all items accounted for, the last step is to turn your to-do-list into a working document. Besides all of the "do" items you already listed, you want to add the task of scheduling any delays. This guarantees that over the next 7 days you will open up your calendar and set dates and times when the delays will turn into do items. Also, create a task to resolve those items you are going to delegate. In some cases it is a 5 minute phone call, but for some items you may want to actually schedule a meeting with whomever you will be putting in charge of the item.

Last, either below or off to the side of your to-do-list, keep some space available to take notes. This will allow you to quickly jot down any new ideas or tasks, allowing you to keep your mind decluttered throughout the week. Then, revisit the 4D process at the end of your week, cleaning up your notes by once again deciding to either do it, delegate it, delay it or dump it.

Can repeated exposure to your name make people like you more? The answer is a resounding yes…well almost a resounding yes. Studies on what has come to be known as the 'mere-exposure effect' or the familiarity principle have demonstrated a strong relationship between frequency of exposure and likeability.

THE SCIENCE In 1968, one experiment exposed participants to a series of Chinese characters, presenting some a single time or up to twenty-five times. The more they were exposed to a particular character, the more they associated the character as having a positive meaning. A key aspect of the study was that participants were not consciously aware of the difference in frequency. Since the 1968 study, over 200 additional studies have been conducted that have verified that from sounds to smells, from tastes, to faces to shapes, typically…familiarity breeds likeability. Notice I said typically breeds likeability. In a 2009 study, it was demonstrated that when perception is already negative, then repeated exposure only serves to reinforce that negativity. In the study, British participants believed they were evaluating how much British people liked French names and vice versa. In one condition they were informed French students had been fair in their ratings and in a second condition were informed that French students had been rating British names as less appealing. The fact is, the French students didn't really even exist. In the first condition, were students thought the French had been fair the mere exposure effect stayed true to form, the more times a name was repeated, the more participants liked the name. But, in the negative condition, the more times a French name was presented, the more they disliked that particular name. APPLICATION For years advertisers have used the mere exposure effect to breed likeability of their product or brand. Instead of spending money across a broad audience, having every person see an ad only once, they buy ads that will be repeated again and again only on certain channels or at specific times as to reach a narrow audience repeatedly. They penetrate the market by being that squeaky wheel you can't ignore. To use the mere exposure effect in your life, consider the following:

|

Authors

Richard Feenstra is an educational psychologist, with a focus on judgment and decision making.

(read more)

Bobby Hoffman is the author of "Hack Your Motivation" and a professor of educational psychology at the University of Central Florida.

(read more) Archives

April 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed